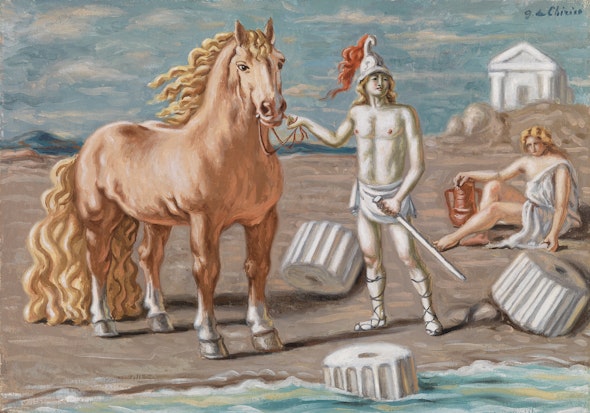

Giorgio de Chirico. Horses of Tragedy (detail), 1935. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

de Chirico’s ‘Horses of Tragedy’

By Kaelin Jewell, PhD, Barnes Foundation art team associate

Located on the east wall of Room 23 is a relatively small oil painting by the Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico called Horses of Tragedy. Created in 1935, the painting was purchased a year later by Dr. Barnes along with another de Chirico called Alexandros, now on the north wall of Room 18. Given that Horses of Tragedy has never been the focus of scholarly inquiry, it was only recently that we’ve been able to bring the mysterious image out of relative obscurity. What we’ve discovered is that the painting, which depicts a group of horses in a mysterious architectural landscape, is most likely related to images of the Christian apocalypse, which de Chirico may have seen as connected to the rise of Italian (or European) Fascism after World War I.

Giorgio de Chirico. Alexandros, 1935. BF960. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Giorgio de Chirico. Horses of Tragedy, 1935. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

In Horses of Tragedy, de Chirico places four different colored horses within an outdoor architectural setting. Each animal is distinct. The black horse enters the foreground while a red horse seems to exit the scene through the opening of a brick-hued arcadelike ancient structure. An ashen-colored horse peers over a black curtain drawn across the upper right corner of the composition, and a grayish-white horse stands with its back toward the viewer inside a rectangular box submerged into the picture's foreground. Along the top of the arcade is a figure dressed as a Greco-Roman soldier who wears a red-plumed helmet and bears a circular shield in one hand and a spear in the other. Running from this figure is a second one, dressed in a togalike garment, who seems to peer back at the soldier.

Giorgio de Chirico. Horses of Tragedy (detail), 1935. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Although Dr. Barnes and Violette de Mazia both commented on the stylistic aspects of Horses of Tragedy and its relationship to ancient Roman and Renaissance traditions, the painting’s enigmatic content was never addressed.¹ It seems likely that de Chirico pulled his subject from a biblical text—specifically, the Book of Revelation 6:1-8 from the New Testament, which describes the four harbingers of the apocalypse riding into the world on the backs of four horses. The first, a white horse, was associated with conquest; the second was red and symbolized war; the third, a black horse, carried a man holding scales and was associated with famine; the fourth was pale-colored and symbolized death.

In Horses of Tragedy, the same four horses are present and set within de Chirico’s vaguely Mediterranean setting while two humans respond violently above. If this reading is correct, we see that de Chirico has placed the black horse, associated with famine, in direct visual dialogue with the red horse of war. While the red horse exits the scene, its head and tail proudly held high, the almost emaciated black horse slowly enters the foreground with its head hanging low to the ground. On the right, the white and pale horse, too, are paired together. Submerged within a coffinlike receptacle, the white horse of conquest, so closely associated with Christ in the middle ages, seems unable to move while the pale horse of death, complete with ashen-colored eyes, peers over a black curtain (a device symbolic of transitory spaces) that gently billows in the directionless breeze. The inclusion of a Greco-Roman soldier chasing a toga-wearing figure, both devoid of facial features, could be a visual reference to how humankind, represented by the military and philosophical classes, might respond to the advent of the apocalypse.

Giorgio de Chirico. Horses of Tragedy (detail), 1935. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

The dreamlike quality of the picture seems to recall the artist’s earlier metaphysical period, which was generally characterized by mysteriously empty Mediterranean spaces that were populated by solitary figures or monumental sculpture. De Chirico’s The Rose Tower from 1913, also in Room 23, is a good example.² In both paintings, we encounter sharply rendered architectural forms drawn from ancient, medieval, or Renaissance spaces. Also, de Chirico’s use of the black curtain in Horses of Tragedy recalls his early metaphysical paintings like The Enigma of an Oracle. In both pictures, black curtains function as barriers, not entirely unlike solid walls, that visually separate the viewer from what lies beyond in the distance. Yet, the viewer knows that the fabric curtains are not solid. The duality present in these motifs, which we find throughout de Chirico’s oeuvre, allows them to function as liminal devices that mark areas of transition between different realms.

Giorgio de Chirico. The Rose Tower, 1913. BF597. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Despite these metaphysical references, de Chirico’s use of horses, so prominently displayed in Horses of Tragedy and Alexandros, caused some critics to see his post-metaphysical period as purely decorative and one that was "catering to wealthy Americans."³ In addition to the connections made to his earlier work, the apocalyptic nature of Horses of Tragedy could reveal the increasing anxiety of Europeans at the rise of Fascism. Although de Chirico aligned himself with the Fascists in 1910, scholars have argued that by the 1920s, works like Gladiators in the Arena and End of Combat (both displayed on the east wall of Room 14) began to hold "up a mirror to Fascist degeneracy and [were] not at all in sympathy with Fascist policy."⁴ Perhaps, therefore, we should understand Horses of Tragedy as a continuation of de Chirico’s anti-Fascist sentiments.

Giorgio de Chirico. Gladiators in the Arena, c. 1925. BF834. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Giorgio de Chirico. End of Combat, c. 1925. BF835. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

In the years following Horses of Tragedy, de Chirico returned to the apocalyptic theme when he produced a series of lithographs in 1941 for L’Apocalisse, an Italian translation of the Book of Revelation.⁵ Of the 20 illustrations, at least two include representations of the horses of the apocalypse, although neither lithograph contains all four of the horses displayed in Horses of Tragedy. Of his 1941 representations of the apocalypse, de Chirico revealed their connection to his earlier metaphysical period:

“I entered the Revelation as if I were in a winter dream . . . a long winter dream that took place in that large, strange house that is the Revelation. . . . I dream, as curious and happy as a boy among his toys on Christmas night.”

Giorgio de Chirico

"Perché ho illustrato l'Apocalisse," Stile, Milan, no. 1, January 1941; translated and reprinted in Jole de Sanna, ed., De Chirico and the Mediterranean (New York, Rizzoli, 1998), 275Endnotes

¹ See Albert C. Barnes, Recent Paintings by Giorgio de Chirico: October 28th to November 17th (New York: Julien Levy Gallery, 1936); and Violette de Mazia, “Tradition: An Inquiry—A Few Thoughts,” Vistas 3, no. 1 (1984-1986): 77-105

² On the metaphysical period, in which de Chirico drew inspiration from Sigmund Freud’s On the Interpretation of Dreams, the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, and artists like Arnold Böcklin and Max Klinger, see Paolo Baldacci, De Chirico: The Metaphysical Period, 1888-1919 (Boston: Bullfinch Press, 1997); and Adriano Altamira, “De Chirico, Böcklin and Klinger,” Metafisica 5-6 (2006): 51-64.

³ Lynda Klich, “De Chirico and Dr. Barnes,” in Giorgio de Chirico and America (1996),” 61.

⁴ For more on de Chirico and his evolving perception of Fascism during the 1920s and 1930s, see Kaela Jewell, The Art of Enigma: The De Chirico Brothers and the Politics of Modernism (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004), 99-101.

⁵ On this and a brief discussion of de Chirico’s illustrations, see Alessandro Scarsella, “Bontempelli e Turoldo, due letture del Vangelo di Giovanni,” in Gli scrittori italiani e la Bibbia, ed. Tiziana Piras (Trieste: EUT, 2011), 157-166.