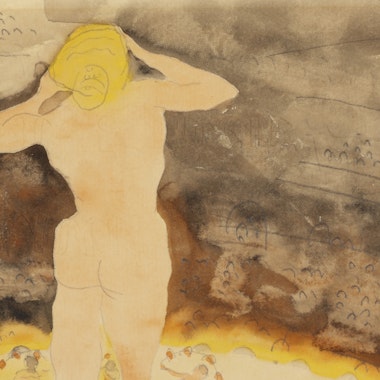

Charles Demuth. Count Muffat’s First View of Nana at the Theatre (detail), 1916. BF1074. Public Domain.

Demuth’s Count Muffat’s First View of Nana at the Theatre

By Lily Scott, Art Team Associate, the Barnes Foundation

The Barnes is known for its extensive holdings of European paintings by Renoir, Cézanne, Picasso, and Matisse. But it’s good to remember that Albert Barnes also focused his attention on many notable American artists, even forging close friendships with several of them. One such artist is Charles Demuth (1883–1935). Born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Demuth is best known for his poster portraits, precisionist cityscapes, and vaudeville watercolors. He was also a gay man, living as openly as possible within the social confines and biases of the early 20th century.

Dr. Barnes and Demuth met in 1905, beginning a close friendship during which Dr. Barnes bought a number of the artist’s paintings—44 remain in the collection¹—and advised him on his health care. Demuth suffered from diabetes, often considered a fatal disease before the discovery of injectable insulin in 1922. Dr. Barnes encouraged him to try this new “serum” being offered by a doctor in Morristown, New Jersey, which improved Demuth’s health for a while. Their friendship continued until the artist’s death in 1935.

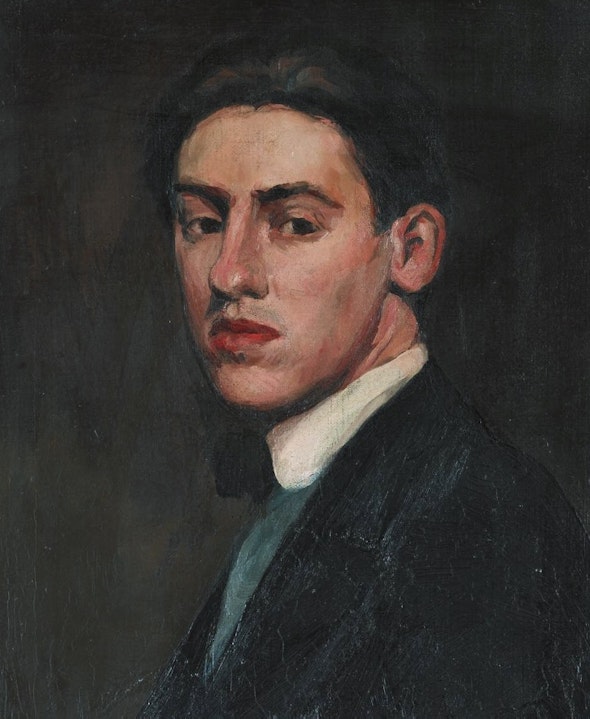

Charles Demuth. Self Portrait (detail), 1907. Public Domain.

A year after meeting Dr. Barnes, Demuth enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he studied under William Merritt Chase and Thomas Anshutz.² By 1914 Demuth had formed a friendly relationship with photographer and art patron Alfred Stieglitz—though he would always remain at the periphery of Stieglitz’s inner circle—and socialized frequently with New York’s elite artists, including Georgia O’Keeffe, Florine Stettheimer, and Marcel Duchamp. In his work, Demuth started to rebel against the standards of American realism, creating more fanciful images of figures and landscapes, often in watercolor. In 1915 Demuth began illustrations based on literary sources.

Demuth’s Nana series (1916), illustrations based on the novel by French author Émile Zola, was exhibited at Manhattan’s Daniel Galleries in December 1920. A newspaper critic noted that “whoever enjoys a whimsical imagination will revel in Mr. Demuth’s illustrations of Zola’s Nana... The man who obtains this group of illustrations will be a lucky man.”³ In March 1922, Dr. Barnes was that lucky man; he acquired eight of the 12 illustrations for his collection.

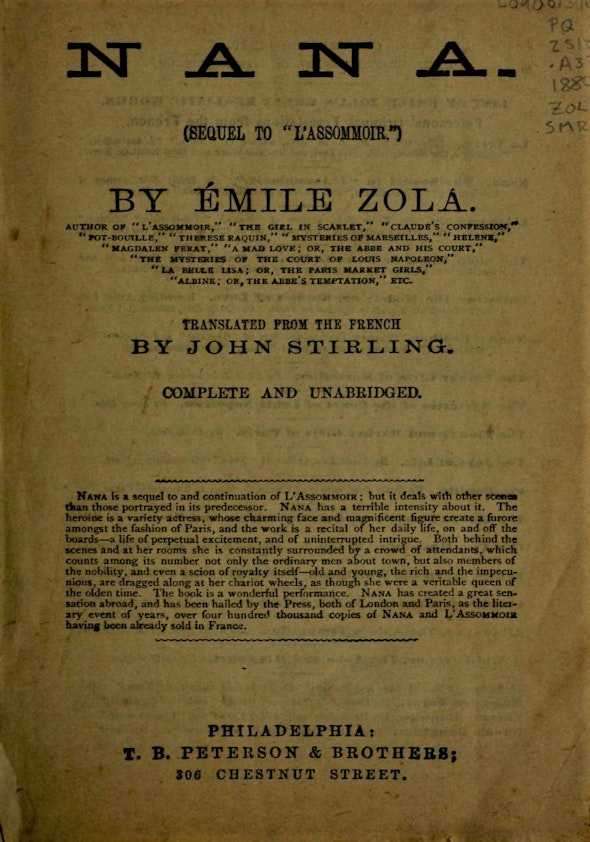

Title page of an English translation of Zola’s Nana.

Written in 1880, Nana tells the story of a young prostitute in Paris who rises to the level of high-class courtesan.⁴ In the novel, Nana meets with countless men, using them for both sexual fulfillment and monetary gain. She often leaves them worse than when she met them—typically in financial ruin. A classic femme fatale, Zola’s character was an emblem of 19th-century anxieties about sexual degeneracy; many blamed the demise of France’s Second Empire on the pleasure-seeking culture cultivated under Napoléon III.⁵ Adding to Nana’s perceived perversion was her same-sex relationship with fellow prostitute Satin.

To further understand Zola’s story—and Demuth’s interpretation of it—we will explore a watercolor depicting a scene from chapter five of the novel. Count Muffat’s First View of Nana at the Theatre is the first illustration in the series, painted in 1916 when Demuth was living in New York’s Greenwich Village.⁶ Though residing in this part of the city provided Demuth with a degree of safety, homosexuality was criminalized at the time.

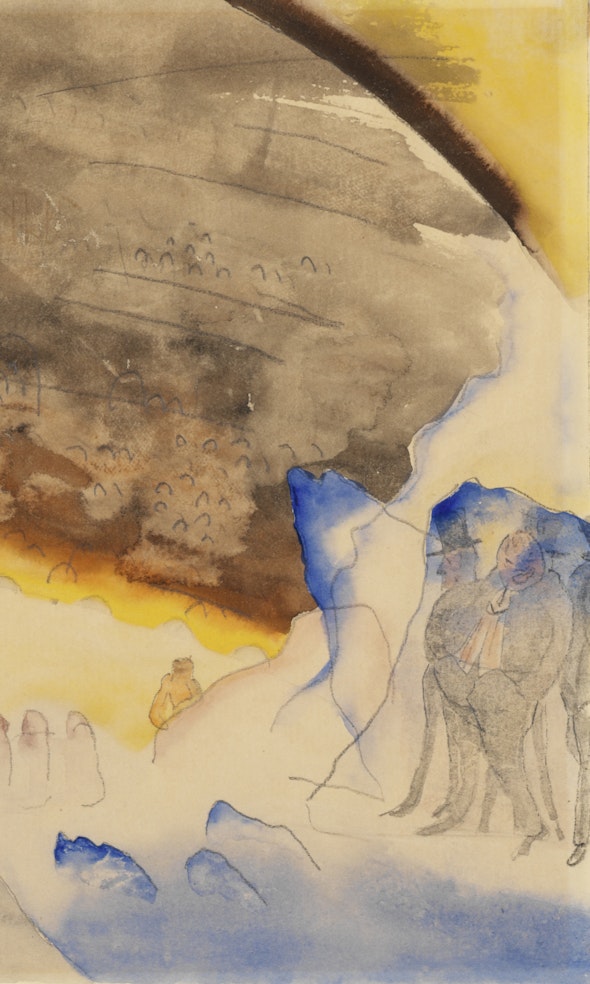

Charles Demuth. Count Muffat’s First View of Nana at the Theatre, 1916. BF1074. Public Domain.

In Count Muffat’s First View of Nana at the Theatre, we see Nana from behind, posed with her hands flanking her face. She stands nude, surrounded by other cast members of The Blonde Venus, a fictional operetta modeled after Offenbach’s La belle Hélène. The audience in the dark theater is barely visible. Demuth’s depiction of the scene differs somewhat from Zola’s description, particularly with regard to Nana. In the novel, she has long, flowing blonde hair and wears a gauzelike fabric around her body for the performance, but Demuth has decided to portray her as nude and with her hair up.

Charles Demuth. Count Muffat’s First View of Nana at the Theatre (detail), 1916. BF1074. Public Domain.

Moreover, rather than representing Nana’s body as the epitome of femininity—with the goddess-like swells and curves that Zola describes—Demuth presents us with an androgynous figure. Art historian Jonathan Weinberg writes that “despite her seductive beauty, she is almost masculine.”⁷ In fact, Demuth’s Nana closely resembles the sculpted male masseur in his painting Turkish Bath Massage, made around the same time. Demuth’s rendering of Nana actively distorts the female body, omitting signs of her sex and feminine attributes and instead emphasizing a chiseled musculature, a more traditionally masculine trait. Demuth likely does this to negotiate and perhaps even evade his discomfort with the sexualized female form.

Demuth’s Nana is reminiscent of some of his male figures.

Charles Demuth. Two Trapeze Performers in Red (detail), c. 1917. © 2019 Estate of Charles Demuth.

By showing Nana from behind, Demuth provides an unmistakably voyeuristic point of view. Voyeurism, at its core, is based on pleasure in looking—and this watercolor is entirely about looking and being looked at. While the audience observes Nana from the front, two men gaze at her from backstage. And, on top of this, Demuth gives us the most voyeuristic view of all: the scene, as a whole, is from the point of view of Count Muffat, who stands backstage and watches Nana through a peephole in the wall.⁸ Demuth indicates the edges of the peephole in the image’s top corners, making it apparent that we, the viewer of the painting, are embodying the role of Count Muffat and therefore the role of the voyeur.

Men gaze at Nana from backstage. Above them, the curve of the peephole adds another layer of voyeurism.

Nana, a novel with an underlying theme of the dangers of sexually powerful women, seems to perfectly coincide with Demuth’s own discomfort with the sexualized female form. Yet as opposed to the countless men in Zola’s novel who fall prey to her erotic prowess, Demuth keeps a safe distance from Nana by viewing her sexuality through a voyeuristic frame.

Endnotes

¹Dr. Barnes also bought 15 others that are no longer in the collection.

²Andrew Carnduff Ritchie, Charles Demuth (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1950), 8.

³Forbes Watson, “At the Galleries,” Arts and Decoration 14-15 (January 1921), 214-215, 214.

⁴It is the ninth work in Zola’s series of 20 novels, Les Rougon-Macquart.

⁵Steven McLean, “ ‘The Golden Fly:’ Darwinism and Degeneration in Émile Zola’s Nana,” College Literature 39.3 (Summer 2012), 61.

⁶Demuth’s studio was in Washington Square; Letters of Charles Demuth, American Artist, 1883-1935, ed. by Bruce Kellner (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000), xv.

⁷Jonathan Weinberg, Speaking for Vice: Homosexuality in the Art of Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and the First American Avant-Garde (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 66.

⁸Art historian and former professor Therese Dolan has referred to this instance in the novel as a “scene of voyeurism and symbolic phallic penetration.” While this paper does not explore the penetrability of the scene, further inquiry into this idea is warranted in future work. Dolan, 376.