Unidentified photographer. Violette de Mazia, Angelo Pinto, and others under Seated Riffian (detail). c. 1930s. Violette de Mazia Collection. Barnes Foundation Archives

Violette Before Barnes:

Early letters and photos from

the Violette de Mazia Collection

By Bertha Adams, Associate Archivist

May 2020

During her 60-year tenure at the Barnes Foundation, Violette de Mazia (French, 1896–1988)¹ served as a teacher, writer, editor, education director, and trustee. She came to the Barnes in the 1920s, in its earliest years of operation, and within a short time secured an appointment to lecture in art appreciation. She also became part of the small contingent of Barnes staff to travel to Europe to study great works of art. Such experiences informed de Mazia’s lectures and writings, which would include four major book collaborations with Dr. Albert C. Barnes—including The Art of Henri-Matisse and The Art of Renoir—as well as numerous articles emphasizing the Barnes method of learning to see.² De Mazia was named director of art education in 1951 and continued to teach until her retirement in 1987.³ She remained a steadfast advocate of Dr. Barnes’s educational mission, earning both praise and criticism for her opinions and practices.

Violette de Mazia, shown in the Main Gallery, began teaching at the Barnes in 1927.

Thanks to newspaper accounts, materials in our archives, and her own writings, de Mazia’s impact and legacy are clear. But who was Violette de Mazia before the Barnes? What was her life like before she came to America in 1924? We found answers to these questions in a relatively new addition to the Barnes archives called the Violette de Mazia Collection, a unique group of papers, photographs, and other materials.⁴ While this collection mainly documents de Mazia’s life at the Barnes, it also contains a significant number of letters written to her in 1923 by Joseph Catz, an aspiring fighter pilot in the British Royal Air Force. Catz was also the love of de Mazia’s life and the tragic figure who altered its course.

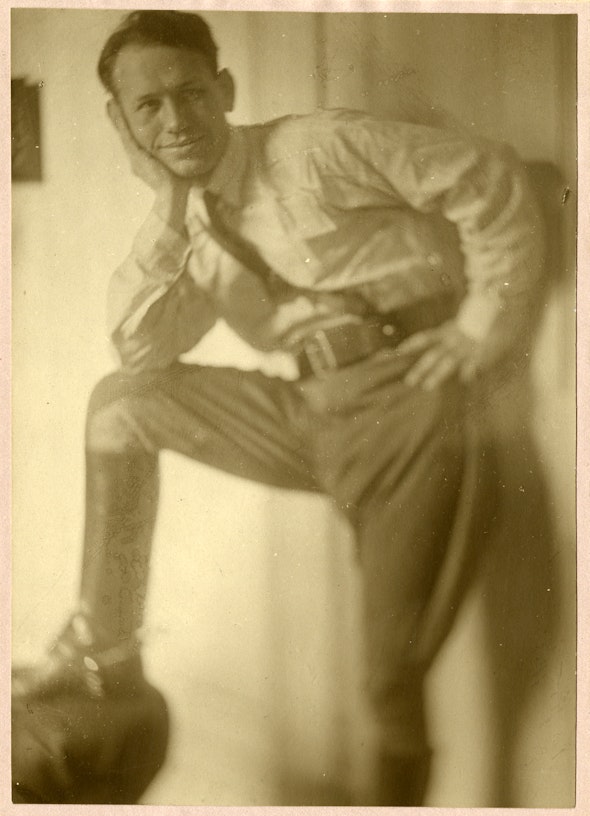

Several photographs of Catz, also part of the collection, show a young man of spirit and self-confidence, matching the impression gleaned from his letters. In contrast, the collection’s only image of de Mazia from this time is a passport photograph. While its intended use undoubtedly influenced the sitter’s expression, the photo echoes characteristics of de Mazia inferred from Catz’s letters—reserve, depth, and self-control. Through these letters and images, we glimpse the young lives of Violette and Joe.

Portrait of Joseph Catz in uniform, 1923.

Joseph Catz was born January 1, 1898, near Cairo, Egypt, to Nathan and Clementine Catz. Unlike a number of Jews living in Egypt at the time, the Catzes were not refugees. Nathan Catz was a well-known international agricultural expert, and the couple were Romanian-born citizens of Egypt.

The younger Catz’s adventurous spirit manifested early on. At age 16, Joe stowed away on a boat sailing to Gallipoli, Turkey, to serve with the Zion Mule Corps during the First World War. He was too young to serve, yet he did so valiantly, and was wounded twice during battle. As to his more formal education, Joe studied in his native Cairo as well as Lausanne, Switzerland, and London. His residency in the latter allowed him to become a naturalized British subject, which in turn gave him the opportunity to seek a commission in the Royal Air Force.⁵

It was also in London, in September of 1920, that Joe met Violette.

This passport photograph of Violette de Mazia, taken in 1922, was affixed to her Declaration of Alien About to Depart for the United States form, 1924.

Violette de Mazia was born outside Paris in 1896 to Jules Sonny Mazia and Fanny Feige Fraenkel, Jewish émigrés who had left Russia with their families during the last quarter of the 19th century. Not long after her birth, Violette’s family, including grandparents, left Paris for St. Gilles, Belgium. In 1902, Violette began attending the primary school in St. Gilles. For the Belgian equivalent of her high school years, she commuted to Brussels for a three-year course of study that included five languages, literature, natural science, and bookkeeping. Her family left Belgium in the summer of 1914, just before the German invasion, and settled in London.⁶

Violette, now 18, continued her study of English at the Priory House School in London, and soon after began teaching there, primarily French and math. Four years later, she passed exams in speaking and writing Italian at the London Polytechnic. She next mastered shorthand at the Pitman School, which was in walking distance of the British Museum.⁷ We know from an admittance pass that Violette visited the museum around this time as a student with permission to sketch in the galleries. To date, there is no other documentation of formal art training for Violette. However, by the time she left London, Violette considered herself an “artiste-peintre.”⁸ No matter her studies in art, it’s more likely that Violette’s language and business skills are what led to her meeting Joseph Catz. Perhaps his father hired her to translate letters for his international business affairs. Whatever the circumstances of the couple’s introduction, we know that for Joe, it was love at first sight.⁹

Joe’s letters to Violette begin in the summer of 1923, when he sailed from England to Egypt for training at Abu Suier air base. From July 20 to December 15—a period of 135 days—he wrote 116 letters, postcards, and telegrams to her. From this correspondence, we learn of Joe’s eagerness to fly solo and his confidence in his skills. We learn of his commitment to the founding of a Jewish state in Palestine.¹⁰ We learn that he desperately wanted to marry Violette and was often frantic at the thought that her parents would not support their union.

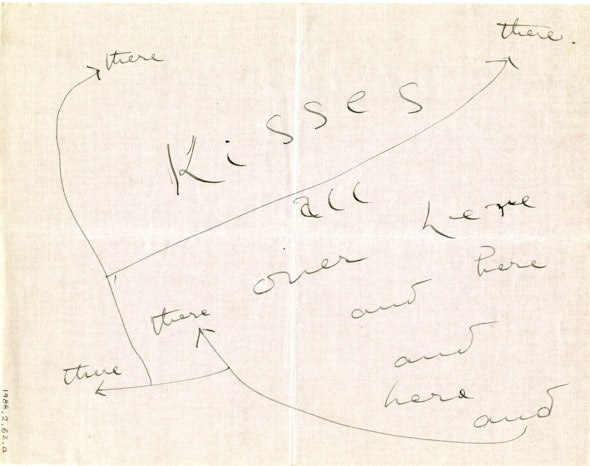

And we learn that Joe had a gift for passionately and playfully expressing his love on paper.

Joseph Catz. Letter to Violette de Mazia, August 24, 1923. Verso of p. 1

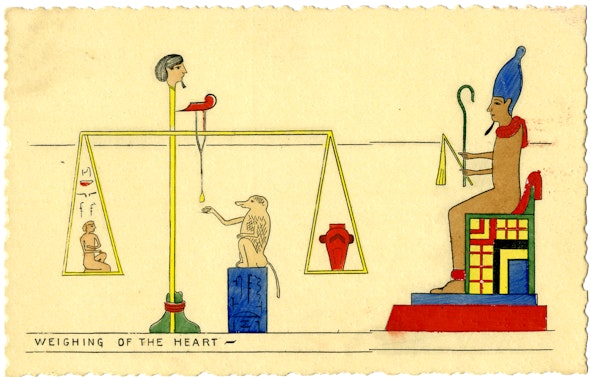

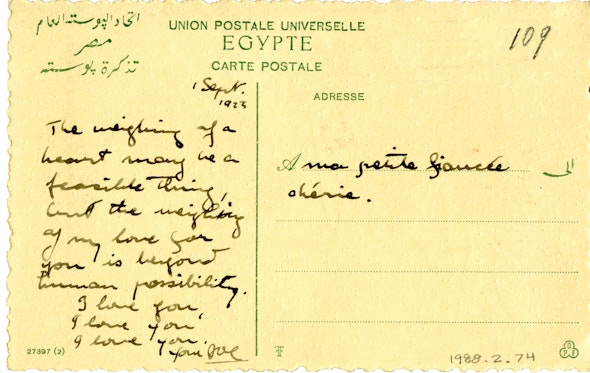

Joseph Catz. “Weighing of the Heart” Postcard to Violette de Mazia, September 1, 1923. Recto and verso. The message reads, “The weighing of a heart may be a feasible thing, but the weighing of my love for you is beyond human possibility”

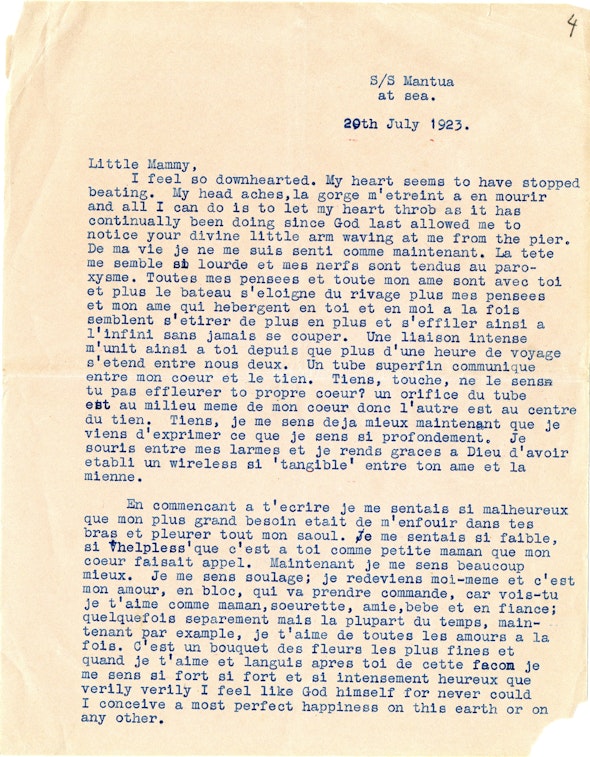

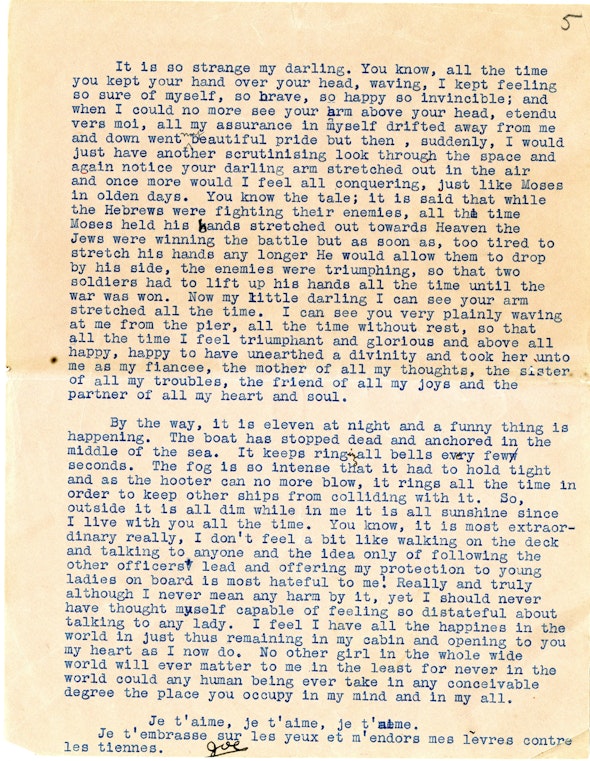

Joe wrote in English and French, and occasionally in Italian, and often switched languages mid-sentence. A good example of this is his first letter, written aboard the SS Mantua en route to Egypt. Unlike most of his letters, Joe typed this one. He begins by telling Violette:

“I feel so downhearted… My head aches, my chest feels squeezed to death and all I can do is to let my heart throb as it has continually been doing since God last allowed me to notice your divine little arm waving at me from the pier…”

Writing in French, he closes the letter:

“I love you, I love you, I love you. I embrace your eyes and fall asleep with my lips against yours.”¹¹

The greeting in this letter, “Little Mammy,” was just one of several terms of endearment used by Joe. In other letters, he refers to Violette as “petite chérie de mon coeur,” “Vio darling,” “ma petite gosse,” and “ma petite fiancée chérie.”

Joseph Catz. Letter to Violette de Mazia, July 20, 1923. Recto and verso

In his next letter, Joe writes, again in French, of his captivation with Violette, even as he struggles with her complexity:

“I fell in love with you the first time I was in your presence. I barely knew you then, and even now perfect knowledge of your soul is a difficult problem I have barely begun to solve… More expressive than words, your eyes, like faithful mirrors, reflect your inner turmoil… But their language is sometimes so obscure and incomprehensible! What haven’t I suffered, even feared from the inscrutability of your expressions!”¹²

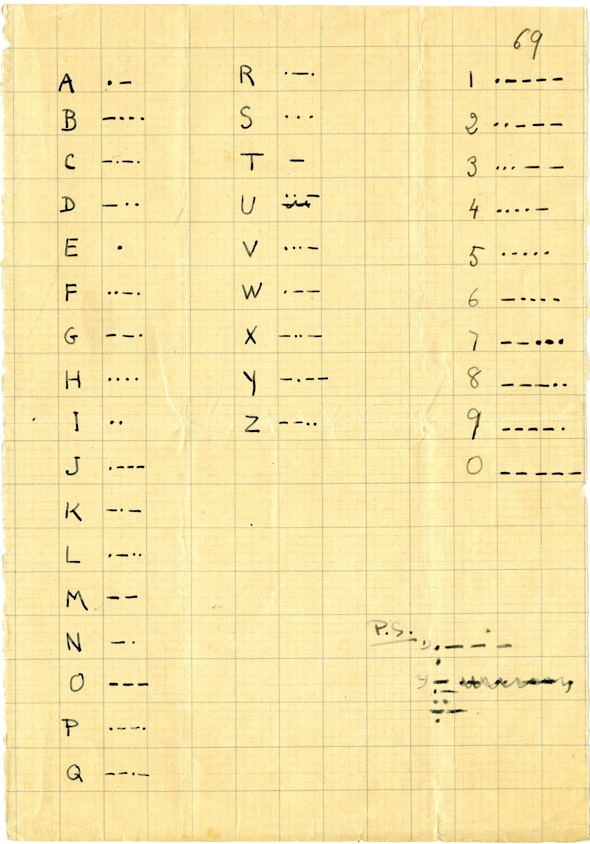

Joe recognized Violette’s intelligence and eagerness to learn. Referring to her as “a living encyclopedia,” he closes his letter of August 16, 1923, with a list of recommendations, explaining:

“I want you to know all I know or am going to know. I. Get proficient in MORSE Telegraph… II. Get a general knowledge of wireless… III. Acquire Hebrew the best you can… IV. Will you excell [sic] in shorthand… [and] V. Get a smattering of gunnery, engines & theory of flight…”

Joseph Catz. Letter to Violette de Mazia, August 16, 1923. Morse code enclosure from four-page letter. Note the coded postscript.

In nearly every letter, Joe expresses his frustration with Violette’s family, particularly her father, for not supporting their desire to marry. He wonders why her father was so opposed. Did he think Joe could not afford the lifestyle to which Violette was accustomed? Was it because Joe was a pilot?¹³ Or was her father alarmed that Joe’s commitment to Zionism and serving in Palestine would take Violette so far from London—for a cause already struggling against anti-Semitism?¹⁴ Despite her family’s lack of approval, Joe never gave up on his plan that they would marry the first day of the following year. The date was significant to him, as it would be his 26th birthday.¹⁵

By mid-September, Joe had decided on a general course of action. He would come to London at the end of December. He and Violette would wed there on the first of January and then return to Egypt, where he had already secured an apartment in the city of Ismaëliah. He would commute to the air base every day, “returning to my little wife after work.” The couple would remain in Ismaëliah until he completed his training, sometime in June 1924. From there, Palestine.¹⁶

Nearly three more months would pass until Violette’s family, father included, finally agreed to the marriage. Joe’s joy, and no doubt relief, come across in his letter to Violette dated December 4, 1923. “What you tell me about his remarks…make me feel that perhaps he really does like me after all and is happy that I am becoming his second son.”¹⁷

Joe would write seven more letters to Violette, the last dated December 15, 1923.

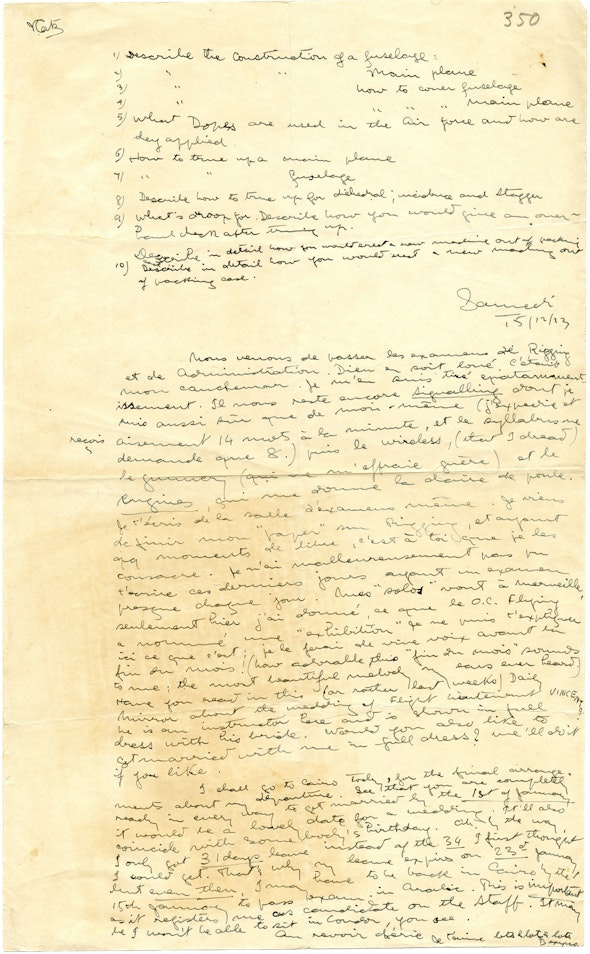

Joseph Catz. Letter to Violette de Mazia, December 15, 1923

At the very top, above the body of his letter, is a list of questions related to his upcoming flight exams. Joe writes the last paragraph in English:

“I shall go to Cairo today, for the final arrangements about my departure. See that you are completely ready in every way to get married by the first of January.”

He closes with, “Au revoir Cherie. Je t’aime lots & lots, Beppo.” (Beppo is a nickname for Giuseppe, which is Joseph in Italian.)

Two days later, a plane piloted by Joe spun to the ground, resulting in a fatal crash.¹⁸ Joseph Catz died just 15 days shy of his 26th birthday—and the day he was to marry Violette.

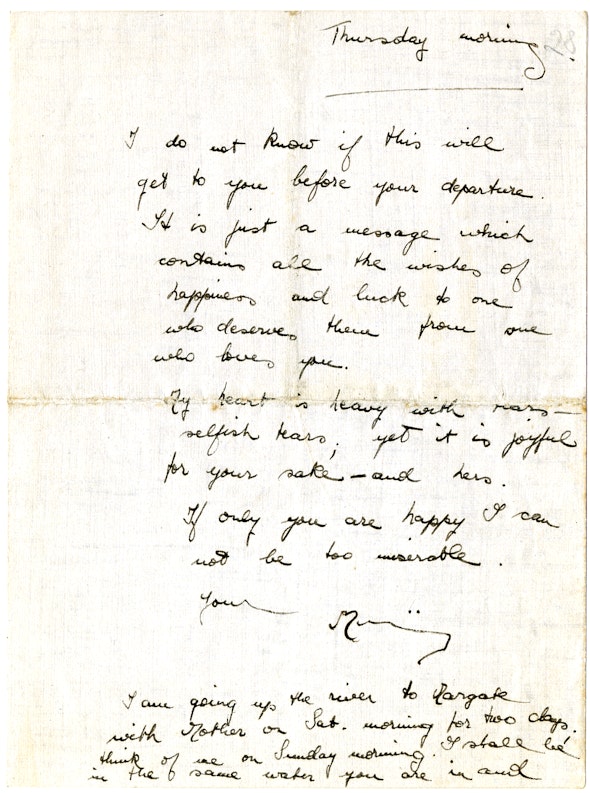

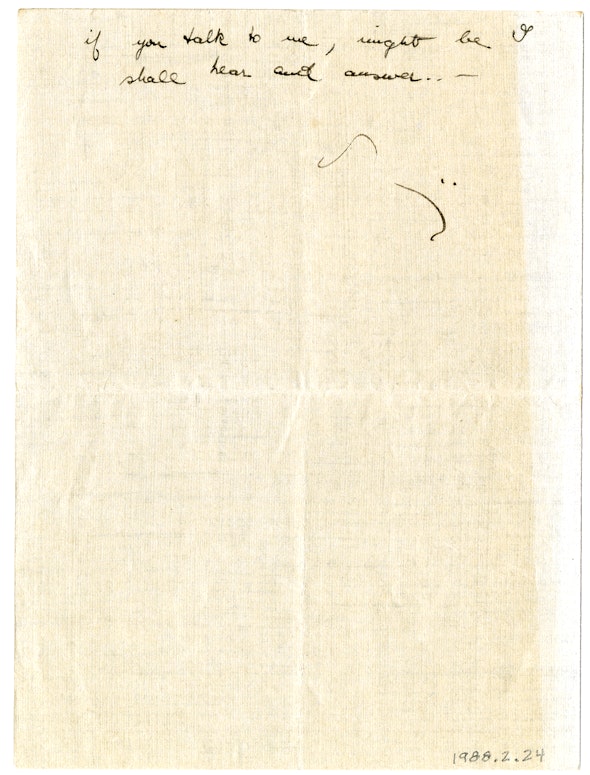

We can tell from Joe’s letters that Violette wrote to him frequently. The whereabouts of those letters, however, is unknown—with the exception of one, which is part of our collection.

Violette de Mazia. Letter to Joseph Catz, [July 12] 1923. Recto and verso

She wrote it just before Joe sailed to Egypt, probably July 12, 1923. It reads in part:

“My heart is heavy with tears—selfish tears; yet it is joyful for your sake... If only you are happy I cannot be miserable.”

She signs it, “Your Mammy.” Violette includes a postscript, which continues on the back of the letter:

“I am going up the river to Margate with Mother on Saturday morning for two days; think of me on Sunday morning. I shall be in the same water you are in and if you talk to me, might be I shall hear and answer.”

We can only wonder what other romantic sentiments young Violette may have composed. What we do know is that Joe’s death dramatically changed her future. Neither England nor Egypt would be her home. Instead, she would remake her life in America, moving to live with relatives in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.¹⁹

Violette de Mazia was nearly 28 when she came to live with her cousins, the Bayuks, in the spring of 1924. Through them, she found work as a French tutor for the daughter of a department store owner. She later taught French and advanced math at a girls’ preparatory school.

By September 1925, de Mazia had secured a position to teach French at the A. C. Barnes Company, which produced Argyrol, the antiseptic that made Dr. Barnes a very wealthy man. At the same time, she began attending lectures at the Barnes Foundation, which had only officially opened in March of that year.²⁰ De Mazia became an instructor herself in 1927 and, from that point on, an indispensable partner to Dr. Barnes and a champion of his progressive approach to art education, which was deeply influenced by the writings of philosopher and education reformer John Dewey.

Angelo Pinto. Photograph. Violette de Mazia teaching in the Cret Gallery in Merion, undated. Pinto Family Donation. Photograph Collection, Barnes Foundation Archives

Over the years, de Mazia developed her own style of teaching. For her first-year and seminar students, she’d wear outfits coordinated with the artworks to be discussed that day. Or use handmade tools to isolate and draw attention to specific sections of a painting—in effect, using interactive devices to enhance visual analysis, much like the digital tools of today. She brought back the Barnes journal in 1970, renaming it Vistas in 1979, and served as a contributing editor until her death in 1988. Even the final three issues, published after her death, included essays by de Mazia, adapted from her lectures. Over the course of 60 years, the young woman who came to America with a broken heart would show countless students how to look at life and art.

Endnotes

¹ De Mazia consistently noted her birth year as 1899, even on her Declaration of Alien About to Depart for the United States form, which she completed on April 9, 1924, for her maiden voyage to the US. However, thanks to the research of Serena Shanken Skwersky, who found de Mazia’s birth record at the French National Archives, we know that she was born August 30, 1896, as Stella Bertha Violette Mazia. See Serena Shanken Skwersky, Remembering Vio: Violette de Mazia: Director of Education and Spirit of the Barnes Foundation (Philadelphia, PA: Kopel Publishing, 2019), 7, endnote 5. Special thanks to Skwersky also for sharing her research notes, which include a number of unpublished translations and primary documentation.

² Dr. Barnes and de Mazia co-authored The French Primitives and Their Forms from Their Origin to the End of the Fifteenth Century (1931), The Art of Henri Matisse (1933), The Art of Renoir (1935), and The Art of Cézanne (1939).

³ De Mazia was appointed to the Barnes Foundation Board of Trustees in 1935. In 1951, after the death of Dr. Barnes, her positions as trustee and director of art education were made lifetime appointments. In 1966, after the death of Mrs. Barnes, de Mazia was named vice president of the board.

⁴ The Barnes Foundation acquired the Violette de Mazia Collection from the Violette de Mazia Foundation in 2015, after the Montgomery County Orphan’s Court granted the latter permission to affiliate its art education program with that of the Barnes.

⁵ Joseph Catz. Letter to Violette de Mazia, November 23, 1923. Violette de Mazia Collection, Barnes Foundation Archives [VDM]. After the First World War, Catz worked as secretary to Vladimir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky (1880–1940), a Zionist leader, orator, and writer who played a significant role in the establishment of the State of Israel. Skwersky, 19–20, and note 27.

⁶ The five languages were French, Flemish, English, German, and Italian. She also studied practical handicrafts, vocal music, gymnastics, and dance. Skwersky, 5–13, endnotes 5, 6 and 13.

⁷ Skwersky, 15–16.

⁸ Admittance to draw in public galleries of the Antiquities departments of the British Museum, 1919. VDM. Mazia identified herself as an artist/painter on a membership dues receipt from the Société Royals des Beaux-Arts (Brussels, Belgium), 1924, and her Declaration of Alien about to Depart for the United States, 1924. VDM. In a deposition taken in 1962, de Mazia stated that she “audited” art classes at the [London] Polytechnic, which the cross-examining attorney misidentified as Hampsted [sic] Polytechnic. Deposition transcripts of Laura Barnes and V. de Mazia (2), 1962. VDM

⁹ Skwersky, endnote 26.

¹⁰ In 1923, Palestine was under British control, as designated by a League of Nations mandate. During WWI, Great Britain had agreed to honor Arab independence in exchange for their revolting against the Ottoman Turks. But in 1917, the British also promised support for a Jewish “national home” in Palestine. The competing interests of the Arabs and Jews and the governing British would lead to revolt in the 1930s and finally the Palestinian war of 1947–49. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mandatory_Palestine

¹¹ Joseph Catz. Letter to Violette de Mazia, July 20, 1923. VDM.

¹² Joseph Catz. Letter to Violette de Mazia, July 21, 1923. VDM. Translation in Skwersky, 18

¹³ “If being in the Air Force displeases him [Violette’s father], this will continue displeasing him for at least another five years!! As for his apparent satisfaction at seeing the presents I sent you, this may very well be because of the proof that I was out of your reach and thus his certainty of overriding my influence over you.” Joseph Catz. Letter to Violette de Mazia, p. 3, September 24, 1923. VDM.

¹⁴ “I am certain, as I have always been, that all your father had against me was my Zionist job.” Joseph Catz. Letter to Violette de Mazia, p. 2, October 25, 1923. VDM. Most evident of Catz’s zeal to serve is a letter to his sister Rose, written a month later to assuage her fears of his flying. “I can foresee in my success a great good that one day will follow me to the land of Israel… I do not have any hesitation to say that I would die happy even in my training period, in order to serve one day in Palestine.” Joseph Catz. Letter to Rose Catz, November 15, 1923. VDM. Translation of letter provided in Skwersky, p. 30–31. As to anti-Semitism, Catz makes a few references to it, usually comments from a fellow officer expressing doubts of Jews serving in Palestine. Yet it did not shake his enthusiasm: “Palestine may be an awkward place for Jews to live in, even officers, yet it is worth while [sic] going there; and then, perhaps is it really a duty to do so and try and prove to the authorities there that there are a certain kind of Jews who are not as black as they are painted, who though in its service are proud of their race and would on no account sacrifice their origin for any consideration.” Joseph Catz. Letter to Violette de Mazia, p. 2, November 26, 1923. VDM.

¹⁵ Joseph Catz. Letter to Violette de Mazia, p. 3, August 5, 1923. VDM.

¹⁶ Joseph Catz. Letter to Violette de Mazia, p. 3, September 15, 1923. VDM. Catz did inquire about being posted to an RAF station in Uxbridge, England, for part of his training. Skwersky, 28.

¹⁷ Joseph Catz. Letter to Violette de Mazia, December 4, 1923. VDM. Skwersky, 33, 36.

¹⁸ Skwersky, 38–41.

¹⁹ She sailed from Southampton, England, on May 17, 1924. Skwersky, 43.

²⁰ The department store was Silverman’s, located at the northwest corner of Sixth and South streets. The school was Miss Saywards School on Drexel Road. Skwersky, p. 43–44. De Mazia was hired to teach French to three female employees at the A. C. Barnes Company—not the Barnes Foundation. Barbara Ann Beaucar, et al., Early Education Records [finding aid, August 2017]. Barnes Foundation Archives. The lectures de Mazia attended were given by Thomas Munro and Laurence Buermeyer, as well as Dr. Barnes. Skwersky, 54.