Joan Miró. Group of Personages (detail), July 9, 1938. BF1187. © 2019 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society, New York / ADAGP, Paris

About Research Notes

Did you know that we are always trying to learn more about our art collection? The Barnes has a team of curators, scholars, conservators, and archivists who are actively engaged in research about the treasured works on view in our galleries. Almost every day we uncover something new—from small details like when an object entered the collection or who may have owned it before, to larger discoveries like unknown sketches on the backs of two Cézannes!

We work constantly to bring new interpretations to works in our collections, linking objects to historical information about the artist or about the time period in which it was made. Barnes Research Notes is a new feature that presents some of our most recent discoveries and theories.

Dr. Barnes, Joan Miró, and the Spanish Civil War

By Brandon Truett, Barnes intern

Hung on the east wall of Room 11, Joan Miró’s Group of Personages (July 9, 1938) and Group of Women (July 15, 1938) are among the more abstract works in the Barnes collection. The paintings present amorphous, vaguely human shapes suspended in a murky, undefined space. As with Miró’s work from the 1920s and early ’30s, the figures appear on the verge of formation, half human, half monster, with occasional moments of recognizable imagery—a face, a torso, an arm—that get swallowed up in the overall ambiguity. If this imagery seems to emerge from the realm of the unconscious, it is at the same time very connected to real-world events.

Joan Miró. Group of Women, July 15, 1938. BF1188. © 2019 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society, New York / ADAGP, Paris

Joan Miró. Group of Personages, July 9, 1938. BF1187. © 2019 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society, New York / ADAGP, Paris

Miró painted these canvases during the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). The Barcelona-born artist was living in Paris at the time, experiencing the violence in his home country through horrifying newspaper accounts of killings and bombings. In both works, the smoky background, imbued with warm oranges and burnt reds, seems to conjure the chaotic aftermath of an aerial bombardment, such as the devastating attack on the Basque town of Guernica on April 26, 1937. The figures gesture wildly toward a hostile sky, undefined except by smoke and fire, and in Group of Women, one figure stretches its tongue as if screaming in pain. Miró has created a dark, confusing environment that evokes the chaos of war and thrusts the viewer into the middle of it.

This figure in Group of Women seems to scream toward the sky.

The painting’s unusual titles and precise dates may also reference the war. Mimicking the international coverage of the war, carried out through newspaper accounts, radio, and film, Miró affixes the paintings within a timeline of battles and bombings, perhaps linking them to specific events. Like Picasso’s Guernica, these paintings draw attention to the fact that for the first time in the history of Western Europe, a civilian population was the target of total war.

But why did Dr. Albert C. Barnes, who is not typically thought of as a politically engaged collector, purchase paintings about a civil war in a foreign country?

Dr. Barnes rarely discussed politics in his writings or personal correspondence, but his actions certainly provide insight into his mind-set.¹ Though it is not widely known, he supported the Spanish Republic’s struggle against General Francisco Franco’s fascist regime. And while we generally accept that Dr. Barnes acquired artworks based on their aesthetic properties, an archival discovery about his anti-fascist actions sheds new light on his purchase of the Miró paintings on May 15, 1939, just a month after the civil war ended.

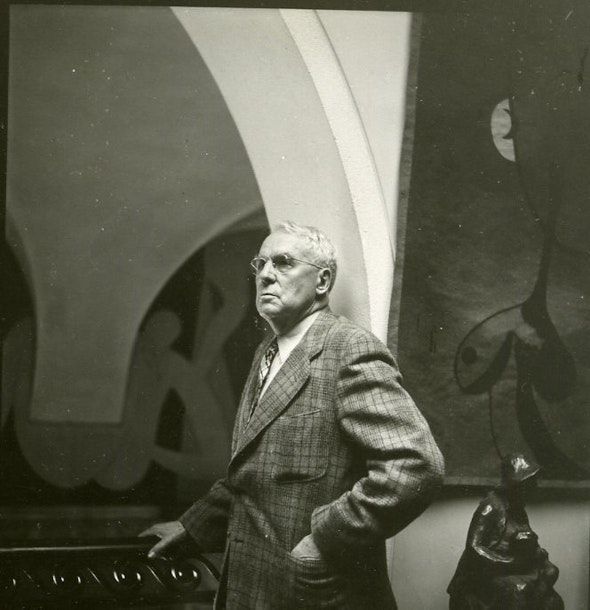

Dr. Barnes stands near a Miró tapestry in Merion, PA. Photograph by Pinto Studios. Photograph Collection, Barnes Foundation Archives

In December 1936, while having a drink in Paris with the gallery owner Étienne Bignou at Harry’s Bar, a popular haunt for artistic expats, Dr. Barnes met José Luis de Cortina, a Basque Loyalist who spoke in great detail about the deteriorating situation in Spain.² In July of that year, backed by the Catholic Church and wealthy landowners, General Franco launched a coup to overthrow the Spanish Republic and replace it with a military dictatorship that would repeal its socially progressive policies. The coup failed to take complete control of the country, and civil war ensued. In August 1936, the well-known poet Federico García Lorca was captured and executed by Franco’s regime, drawing international attention to the conflict. The bloody three-year civil war is now recognized as a prelude to World War II.

Cortina in 1937

Galvanized by his discussion with Cortina, Dr. Barnes decided to facilitate “American propaganda” to garner international support for the Republican cause.³ Many Western democratic nations, such as England and France, had committed to a policy of non-intervention—even though Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy provided military aid to Franco. To circumvent this policy, nearly 40,000 volunteers joined the fight through the International Brigades. American writers, such as Martha Gellhorn, Ernest Hemingway, and Langston Hughes, reported on the Republic’s efforts to resist fascism.

Upon his return to Philadelphia, Dr. Barnes wrote to Bignou, indicating his excitement at having successfully recruited his friend, the journalist Henry Hart, to cover the events in the Basque Country for progressive American newspapers like the New Republic. As Dr. Barnes put it, “I never expected to have such luck as this and I doubt if the Basque people had either.”⁴

Dr. Barnes helped Hart acquire a visa and delegated Georges Keller of the Bignou Gallery as his proxy in case Hart needed money or further diplomatic assistance. Hart traveled to Bilbao from France in late February 1937, but he stayed for only ten days, accepting the Basque authorities’ recommendation to leave. On March 1, Hart sent an emergency cable to Dr. Barnes, imploring him to discuss the dire situation in person.⁵Dr. Barnes was infuriated by Hart’s abrupt departure from Bilbao, which he regarded as a “thorough-going fizzle.” In his excoriating reply to Hart, Dr. Barnes wrote, “I cannot imagine a newspaperman of your ability, transplanted into that atmosphere, and having contact with the Basque authorities, failing to utilize available material in a way that would make the cables tingle.”⁶Hart’s inability to deliver an effective account of the civil war prompted Dr. Barnes to lose hope in the Republic, and he refused to speak further about the situation.

In November 1937, Barnes received a distraught letter from Cortina, who had been captured by Franco’s regime upon his return to Bilbao. Cortina spent more than three months in a political prison before fleeing to France through the Pyrenees mountains. Appealing to Dr. Barnes’s “sympathy … for my poor country and our people,” Cortina asked for assistance to relocate to the US and find work.⁷ There is no record of Dr. Barnes’s response to Cortina, but as the Nazi occupation advanced in 1940, Dr. Barnes did help artists such as Jacques Lipchitz and Marie Cuttoli escape France.

In 1963, Hart published the biography Dr. Barnes of Merion: An Appreciation, in which he recounts his brief time in Spain. Hart recalls that Dr. Barnes donated money to send ambulances to the Spanish Republic and when asked why, he responded, “I do it . . . because of the heroism of the Spanish people.”⁸ The defeat of the Spanish Republic was likely a profound disappointment to Dr. Barnes, who shared its progressive views toward education and social justice. He may have been drawn to Miró’s uniquely political paintings—the forlorn figures with flailing gestures, the dark skies with their unseen threat—because of his enduring sympathy for the Spanish people. Indeed, although the civil war ended in 1939, Spanish society today continues to deal with the ramifications of Franco’s victory and the ensuing decades of fascist rule.

Endnotes

¹In an extensive review of Dr. Barnes’s correspondence, researcher Zachary Ford uncovered information about Dr. Barnes’s participation in relief efforts during both world wars; Ford also noted that Dr. Barnes rarely wrote about his political views.

²Correspondence between Dr. Barnes and Étienne Bignou in January 1937 reveals that this meeting took place and the large extent to which Bignou facilitated Dr. Barnes’s receipt of more information about the Spanish Civil War. See Étienne Bignou, letter to Dr. Barnes, January 5, 1936 (likely misdated).

³José Luis de Cortina, letter to Dr. Barnes, January 30, 1937, Albert C. Barnes, Correspondence, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, PA.

⁴Dr. Barnes, letter to Étienne Bignou, January 20, 1937, Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, PA.

⁵Henry Hart, letter to Dr. Barnes, March 1, 1937, Albert C. Correspondence, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, PA.

⁶Dr. Barnes, letter to Henry Hart, March 18, 1937, Albert C. Correspondence, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, PA.

⁷José Luis de Cortina, letter to Dr. Barnes, November 6, 1937, Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, PA.

⁸Henry Hart, Dr. Barnes of Merion: An Appreciation (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Company, 1963), 158. This quotation is derived from Hart’s recollection and therefore should be taken as paraphrasing Dr. Barnes’s own words.