Dr. Albert C. Barnes, 1942. Photograph by Angelo Pinto. Courtesy of the Pinto family. Photograph Collection, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia

Rancor, Returned Letters & Reconciliation:

Dr. Albert C. Barnes and Leo Stein’s Correspondence

By Rob Jagiela, project assistant, Archives, Library, and Special Collections

The Barnes Foundation’s Archives, Library, and Special Collections (ALSC) Department houses a wealth of resources available to staff members and external researchers. Among these resources, the crown jewel is the Albert C. Barnes Correspondence. The Correspondence is one of the ALSC’s most frequently requested and referenced resources. It documents, through copious exchanges with prominent artists, dealers, and critics, the creation of Dr. Barnes’s world-renowned art collection, the formation and growth of his progressive educational program, and the establishment of the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania. Spanning almost 50 years (1902–1951), the Correspondence is vital to the history of art and to histories of museums and collecting.

As part of ongoing efforts to make our collections and resources more widely accessible to both staff and external researchers, in 2021 the ALSC team embarked on a multiyear grant project titled Dear Dr. Barnes: Digitizing, Interpreting, and Disseminating the Albert C. Barnes Correspondence. By July 2022, the Correspondence’s more than 22,000 files had been digitized, resulting in the creation of a corresponding PDF file for each physical file in the archives. With digitization complete, we turned our attention to providing access to these new resources. Earlier this year, we launched the Albert C. Barnes Correspondence Spotlights, the first of which focused on Dr. Barnes’s communications with philosopher John Dewey and with art critic and collector Leo Stein.

One goal of the Spotlights is to present the Correspondence and the stories therein to audiences who may not interact with the archives otherwise. Now that this resource is available online, we can use the letters sent between Leo Stein and Dr. Barnes to tell the story of their relationship, including its high points and low points, from friendship to hostility back to friendship again.

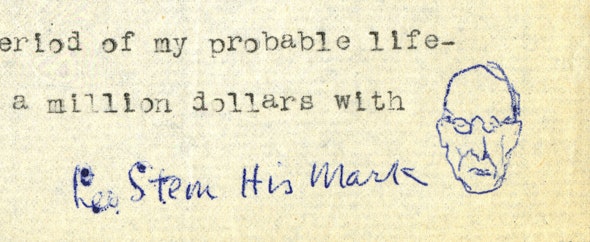

Detail of Stein’s signature with self-portrait doodle. Leo Stein to Albert C. Barnes, March 29, 1946. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence

Dr. Albert Barnes and Leo Stein first met in 1912. In the spring of that year, painter William Glackens had traveled to Europe to purchase paintings on Barnes’s behalf. Barnes was enthralled by the works found by Glackens, who urged the collector to observe the art scene himself. Later that year, Barnes made the first of what would be many trips to Paris to purchase new works for his collection.

Stein, an art critic and collector, had settled in Paris several years earlier in 1903, with his sister Gertrude. They lived together at 27 rue de Fleurus, in an apartment that also served as a studio and entertaining space for artists whose work would come to define modern art and literature, such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, James Joyce, and Ezra Pound. Although many guests were attracted to the Stein salon by Gertrude’s magnetic personality, it was Leo who formed a lasting connection with Dr. Barnes.

Henri Matisse. The Sea Seen from Collioure, 1906. BF73. © 2023 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Henri Matisse. Dishes and Melon, 1906–07. BF64.© 2023 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

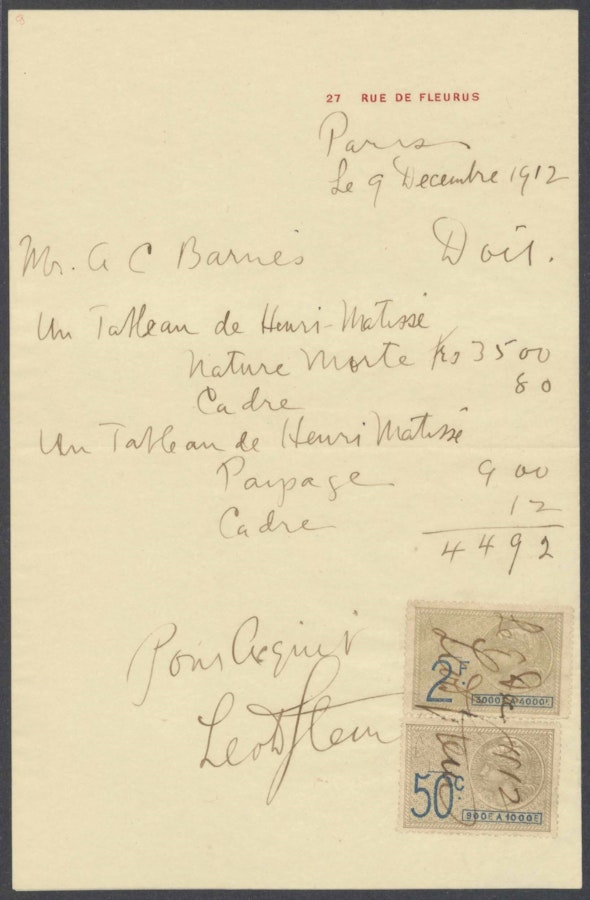

Through the years, the correspondence reflects multiple aspects of their relationship: the practical, with Leo Stein sourcing and selling artwork to Barnes, as well as the personal, with the two exchanging theories on art and aesthetics. The first piece of correspondence comes the year of their meeting and documents Barnes’s purchase of the first two of many Matisse paintings that would enter his collection: The Sea Seen from Collioure (BF73) and Dishes and Melon (BF64). (Brenda Wineapple writes that Gertrude espied the depth of his pockets and insisted on selling Barnes both paintings, not just one.¹) Quickly and frequently, however, their letters turn from the business of dealing art to long discussions centered on aesthetics and psychoanalysis.

Receipt, Leo Stein to Albert C. Barnes, December 9, 1912. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence

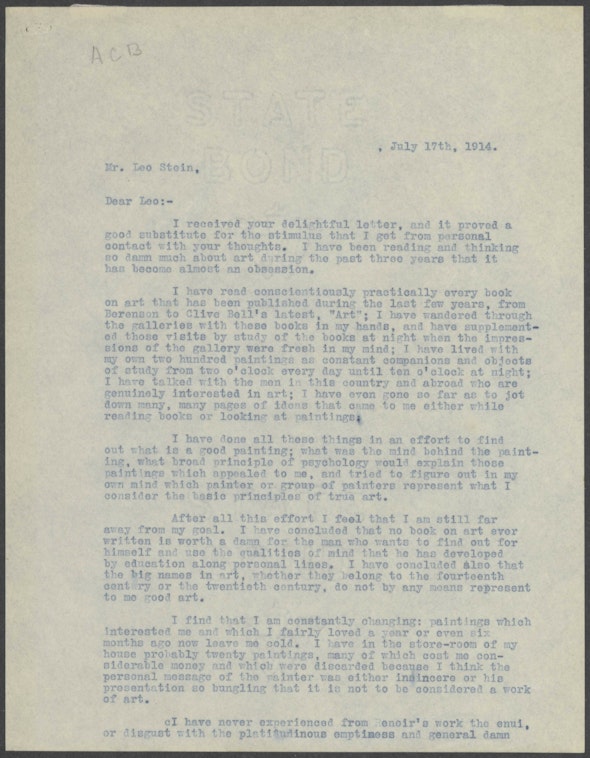

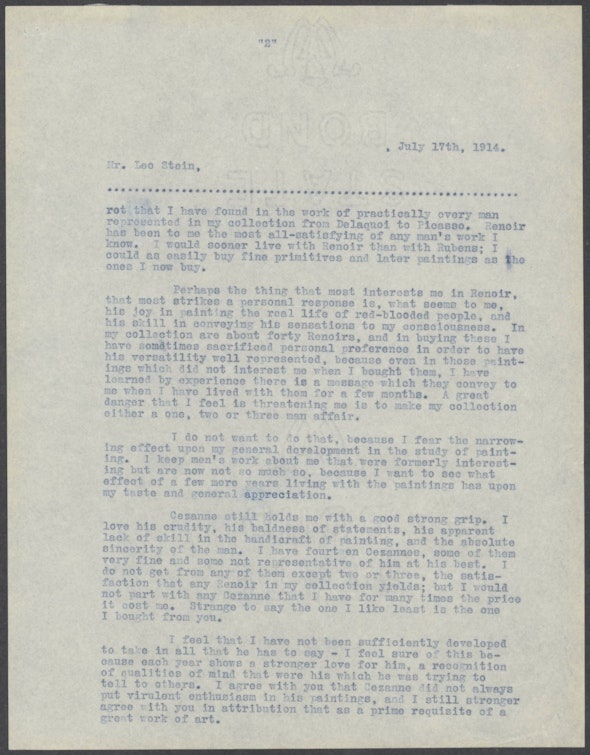

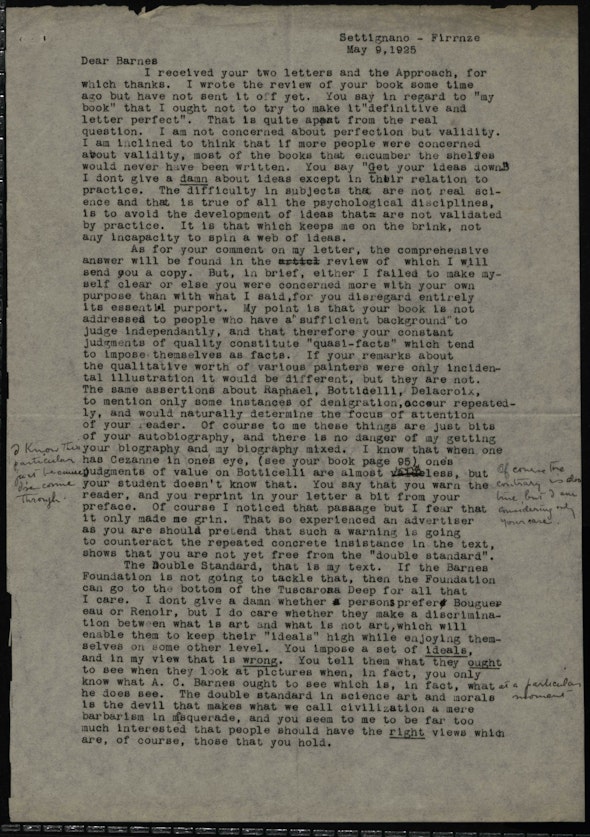

In much of their correspondence, Barnes comes across as the dominant personality in the relationship; however, a July 1914 letter written by Barnes indicates this was not always the case. Instead, Stein appears to be the more experienced of the two, with Barnes working to catch up to him. Stein had been purchasing and analyzing art for several years by that point, while Barnes had only begun seriously purchasing art the year the pair met. Stein’s opinions on aesthetics were also solidified, while Barnes’s were still in formation—the strength of Stein’s opinions had even been a contributing factor in his recent split from Gertrude.

As a result, the letter exhibits a sense of humility and introspection on Barnes’s part that would later be replaced by ego bolstered by the success of his foundation. Barnes opens: “I received your delightful letter, and it proved a good substitute for the stimulus that I get from personal contact with your thoughts. I have been reading and thinking so damn much about art during the past three years that it has become almost an obsession.”²

Among the works that Barnes would have been reading at this time were those of Bernard Berenson and William James, who both served as role models for Stein.

Additionally, Barnes empathizes with Stein over a shared sense of isolation. After Leo and Gertrude went their separate ways, Stein’s existence took up the nomadic quality it had before the pair settled in Paris, causing him to be isolated from his circle of friends, which was already quite small compared with the court held by Gertrude. In his July 1914 letter, Barnes continues:

“I am almost alone in this entire continent in collecting paintings such as mine. . . . I read with interest the account of your lonely life, but you have very little on me in that respect. . . . I have absolutely no social life, and except for a few friends like Glackens and some of the other artists who drop in on me for a day or two, I am as lonely as you are with your lettuce patch.

For that reason and for other more positive and personal ones, I would like mighty well to get a letter from you once in a while.”³

Letter, Albert C. Barnes to Leo Stein, July 17, 1914. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence

Barnes did indeed continue to get letters from Stein, often more frequently than “once in a while.” However, Barnes’s tone became less fraternal and introspective over the years. Instead, a new side of their relationship emerged: one in which the two men pitted themselves and their opinions against the other, despite the closeness of the aims and goals that motivated the expression of such opinions.

Though they both sought to bring art education and appreciation to the masses, they could never seem to agree on the methods or language that should be used to do so.

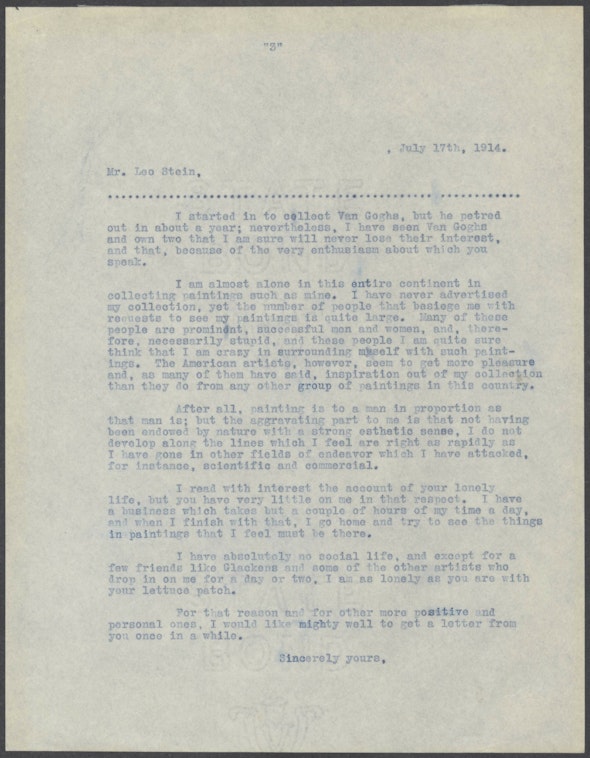

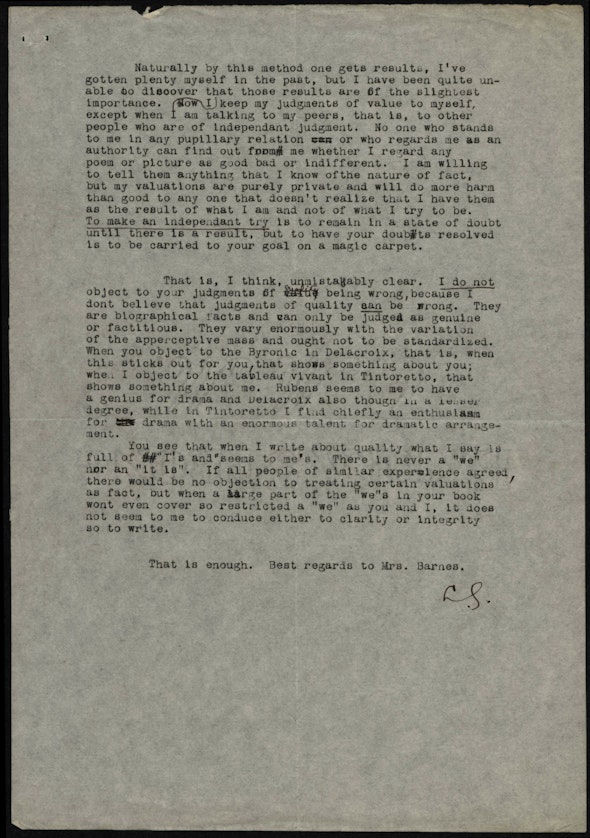

The adversarial tone of their correspondence reached a fever pitch in 1925. Early that year, Barnes had published The Art in Painting, the central text for his foundation’s nascent education program, in which he sought to apply the principles of scientific analysis to art and art appreciation, forming the basis for what today we call “the Barnes method.” In April, Stein let Barnes know that he planned to review the book. He wrote: “It is going to be a very favorable notice of the analytic part of it followed by a discussion of the imposition of valuations as a factor in education. In regard to this I take issue with you rather decidedly.”⁴ Stein explained that although he endorsed the book overall, he felt Barnes relied too heavily on his use of “we,” employing it as a method of persuading readers to share in his judgments of quality and value without providing sufficient objective support. In a later letter, Stein clarified: “My point is that your book is not addressed to people who have a ‘sufficient background’ to judge [independently], and that therefore your constant judgments of quality constitute ‘quasi-facts’ which tend to impose themselves as facts.”⁵

Surprisingly, based on the vitriol to come, Barnes seemed to take the criticism in stride in his initial response. He thanked Stein for the “good news” that he would be reviewing The Art in Painting and even acquiesced to some of Stein’s criticisms: “Your strictures on my book I admit to a certain extent.”⁶ However, his response also defended the book and offered justifications for his reasoning:

“Another point to bear in mind is that the book is merely something to start on in the educational problem that the very start of the Foundation imposed upon us. Not a damned thing can be accomplished by merely writing about pictures. All I wanted to do was to have something to start people to look at pictures and, of course, to get the psychological background.”⁷

Stein, for his part, was not satisfied with Barnes’s justifications. In fact, he seemed more invigorated in his criticisms by Barnes’s responses. Stein wrote: “Either I failed to make myself clear or else you were concerned more with your own purpose than with what I said, for you disregard entirely its essential purport.”⁸ To Barnes’s assertion that he informed readers in the book’s preface that the goal was to give them tools to reach their own conclusions, and not to present his own as fact, Stein responded, “That so experienced an advertiser as you are should pretend that such a warning is going to counteract the repeated concrete [insistence] In the text, shows that you are not yet free from the ‘double standard.’”⁹

Letter, Leo Stein to Albert C. Barnes, May 9, 1925. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence

Barnes seemed to take Stein’s response as a signal that the time for constructive critical dialogue had passed and that the two had entered into an all-out quarrel. He drafted a number of responses to Stein; in one typed letter that is crossed out in pencil and contains the note “not sent,” Barnes wrote:

“What I mean is that you live in a vacuum, the soft, pathetic life of the Florentine and Parisian expatriate ruined you years ago. You have dodged life and you cannot at the age of fifty-three start anew to get “experience” nor to get a knowledge of what “science” or “scientific method” really means. . . . I fear that now, as then, your values are tied in knots. But you would be a nice fellow if you didn’t think you are so damned bright.”¹⁰

He closed the unsent letter facetiously: “Don’t bother me now with letters because I am busy forcing my opinions down the throats of a lot of poor boobs who seem interested in paintings.”¹¹ In the version he did end up sending, Barnes condensed his sentiments to the following: “In short, it is a safe bet that your review will not be a criticism of the contents of the book but a revelation of the psychology of a man who has lived in a vacuum while the world went marching on.”¹²

At this point, Stein and Barnes largely stop communicating directly, instead both writing to philosopher John Dewey about their issues with the statements of the other. Stein reiterates many of his criticisms of The Art in Painting to Dewey. Dewey in turn shares his letter with Barnes, who seems ready to take the fight back up after several months of silence. Stein, however, had had enough. His review of The Art in Painting was due to be published in the December 2 issue of the periodical The New Republic, and as he stated in earlier letters to Barnes, he wanted it to stand as his final comment on the matter. From previous experience, Stein knew that he could never win an argument with Barnes by continuing to argue his point, no matter how clear it seemed in his mind. The only way to move past a disagreement after it had reached such a boiling point was to cease further conversation about the matter.

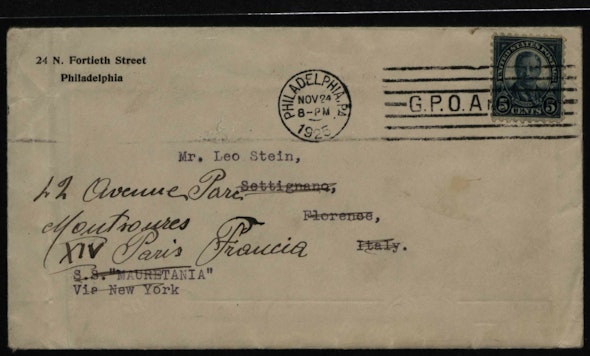

On November 24, Barnes wrote to Stein. Stein refused to engage and returned the letter to Barnes unopened. On the back of the envelope, Stein wrote: “After the characteristic specimens of self-defensive vituperation last summer, I decided to receive no further communications from you.”¹³ He explained that, as he saw it, they each took some jabs at the other and tempers flared, but that continued “random movements of vituperation” would not resolve any issues.¹⁴ However, Stein could not resist one last jab of his own. In closing, he praised Barnes associate and collaborator Laurence Buermeyer’s book The Aesthetic Experience and suggested that Barnes would do well to absorb some of its contents into his own “way of being.” Stein quipped, “A little genuine self-culture would be an excellent preparation for the boss of the Barnes Foundation.”¹⁵

Returned envelope, Leo Stein to Albert C. Barnes, November 24, 1925. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence

As for the unopened letter, the contents remain unknown. As archivists, we seek to organize and preserve the records of past activities to better understand them in the present day. In the field, opinions on the subject of opening sealed letters vary greatly, and depend on a number of factors, including the context in which the letters were sent or received and the risk of damage to the original object if it were opened. Our archivists have chosen to keep the letter returned by Stein sealed. Opening the envelope would likely disrupt the message written by Stein on its back. Further, given the context and the history of Barnes and Stein’s relationship, one can assume that Barnes’s letter mostly contains attacks on Stein’s character and mental faculties similar to those he’d already been hurling his way.

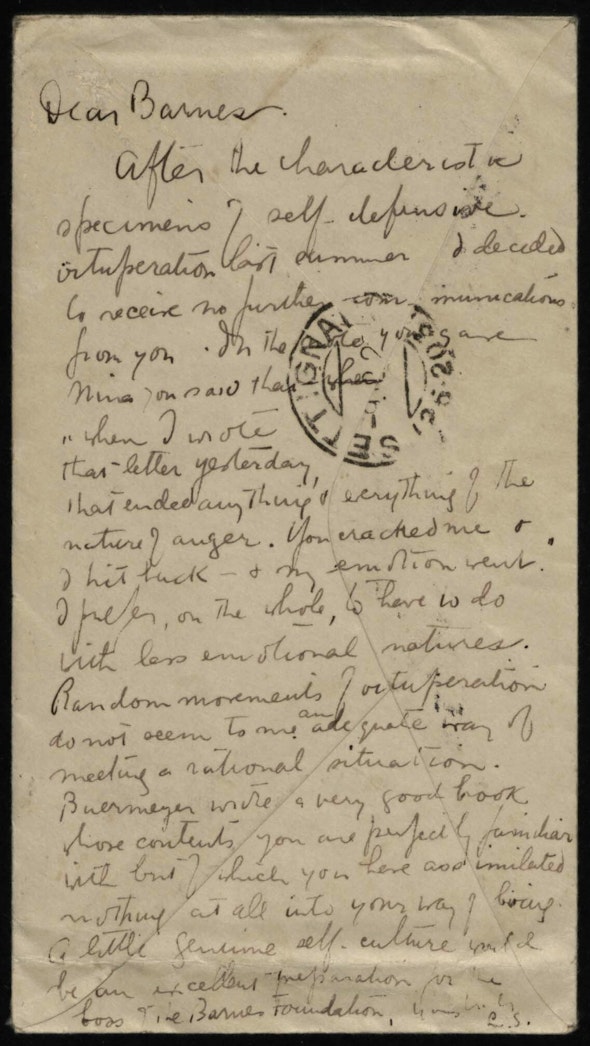

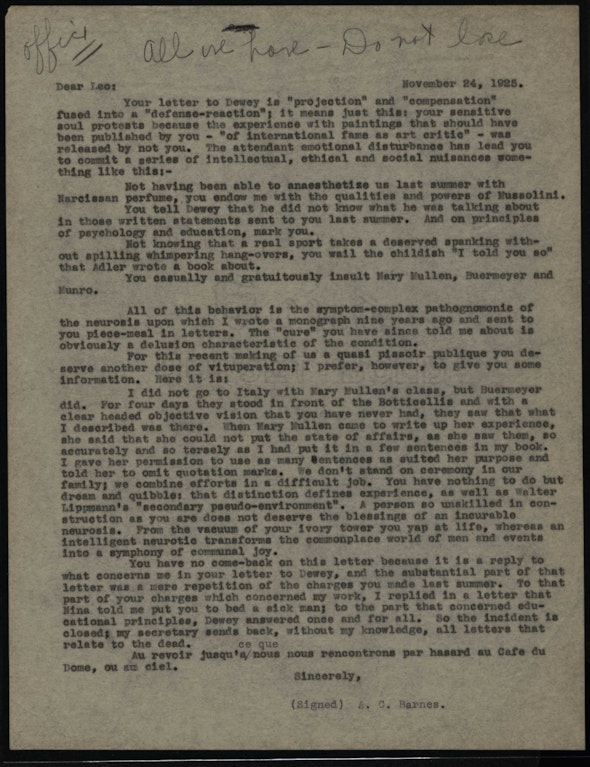

The best argument for leaving the envelope intact, however, is that we may have a copy of the original letter, thanks to Barnes’s penchant for keeping duplicates of his own letters to later circulate to friends and periodicals. On December 17, 1925, Barnes wrote a note to Leo Stein and sent a copy to his secretary Nelle E. Mullen. He included a handwritten message for Mullen, saying that he had seen Stein’s wife, Nina, learned of the unopened letter, and would be sending another copy to Stein, since “nearly everybody else we know in America got one.”¹⁶ Based on this note, it seems likely that a letter in the archives addressed to Stein and dated November 24 (the same date as the first mailing) is in fact a copy of Barnes’s original letter. This theory is bolstered by handwritten notes from Mullen on the letter that read “office” and “All we have – Do not lose.”¹⁷ If this letter is indeed a copy, it seems for the best that Stein left it unread—it contains some of Barnes’s most personal insults related to their quarrel. Barnes closes by saying that his secretary sends back “all letters that relate to the dead,” and writes in French that perhaps they’ll see each other in heaven, indicating that as far as he is concerned Stein is dead, and their relationship dead with him.¹⁸

Letter, Albert C. Barnes to Leo Stein, November 24, 1925. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence

Barnes and Stein would not communicate directly again until 1934, nearly a decade later. However, for all of their vitriol, the two had apparently not lost all goodwill for the other. Barnes dedicated his 1933 volume The Art of Henri-Matisse to Stein, writing “To Leo Stein, who was the first to recognize the genius of Matisse and who, more than twenty years ago, inspired the study which has culminated in this book.”¹⁹ In autumn of 1934, Stein wrote to Barnes, having heard of the book and its dedication through the grapevine. Barnes responded that he was glad to hear from Stein, and that he would send him a copy right away. He recapped his and the Foundation’s recent activities before writing, “I often think of you, wonder what you’re doing and wish I could talk to you from time to time.”²⁰ With that, the two resumed their exchanges, interrupted only by disturbances in transatlantic postal services during World War II. Even during wartime, however, the two continued to correspond, with Barnes sending care packages of food and books to Stein and his wife in Italy.

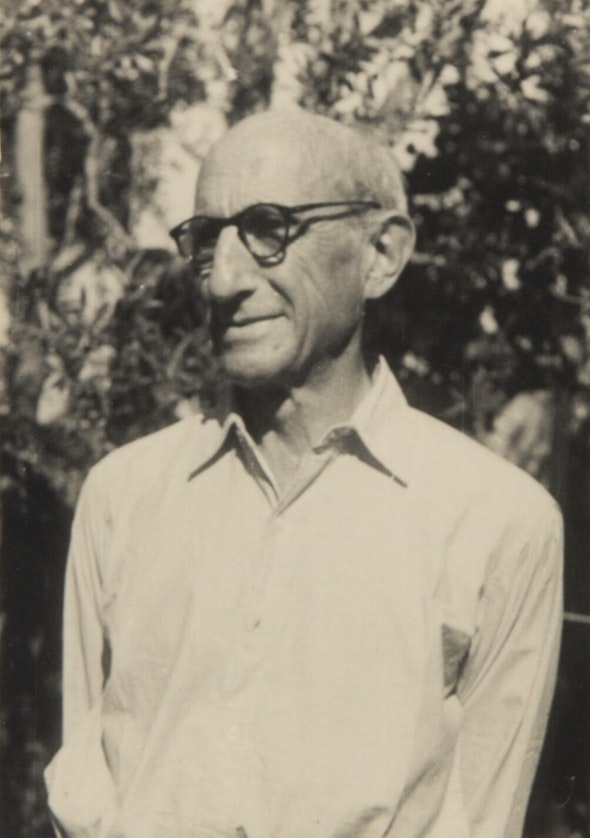

Leo Stein in Settignano, Italy, c. 1946–47. Leo Stein Collection. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

This story of Barnes and Stein’s friendship, quarrel, and reconciliation is just one of thousands that can now be discovered and told thanks to the digitization of the Albert C. Barnes Correspondence. With this new resource available to researchers and public access points being rolled out, the possibilities for scholarship will only continue to grow. We invite you to explore the Correspondence Spotlights, containing the letters between Dr. Barnes and Paul Phillipe Cret, John Dewey, Paul Guillaume, and Leo Stein. We also invite you to explore the exhibition Education & Empowerment: Scholarship Recipients at the Barnes Foundation, 1927–1949, which draws on archival materials to highlight the diverse experiences of four individuals who had their education supported by the Barnes Foundation in the first half of the 20th century. The exhibition is on view at the Barnes through August 2024 and is also available online.

Endnotes

¹ Brenda Wineapple, Sister Brother: Gertrude and Leo Stein (University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 377.

² Albert C. Barnes to Leo Stein, July 17, 1914. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia (AR-ABC-1914-118)

³ Ibid.

⁴ Leo Stein to Albert C. Barnes, April 13, 1925. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia (AR-ABC-1925-843)

⁵ Leo Stein to Albert C. Barnes, May 9, 1925. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia (AR-ABC-1925-843)

⁶ Albert C. Barnes to Leo Stein, April 27, 1925. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia (AR-ABC-1925-843)

⁷Ibid.

⁸ Leo Stein to Albert C. Barnes, May 9, 1925. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia (AR-ABC-1925-843)

⁹ Ibid.

¹⁰ Albert C. Barnes to Leo Stein, June 4, 1925. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia (AR-ABC-1925-843)

¹¹ Ibid.

¹² Albert C. Barnes to Leo Stein, June 5, 1925. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia (AR-ABC-1925-843)

¹³ Leo Stein to Albert C. Barnes, after November 24, 1925. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia (AR-ABC-1925-843)

¹⁴ Ibid.

¹⁵ Ibid.

¹⁶ Albert C. Barnes to Leo Stein, December 17, 1925. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia. (AR-ABC-1925-843)

¹⁷ Albert C. Barnes to Leo Stein, November 24, 1925. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia (AR-ABC-1925-843)

¹⁸ Ibid.

¹⁹ Albert C. Barnes and Violette de Mazia, The Art of Henri-Matisse (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1933), Dedication.

²⁰ Albert C. Barnes to Leo Stein, October 4, 1934. Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia (AR-ABC-1934-507)