German. Tankard (detail), 1766. 01.11.60. Public Domain.

Dr. Barnes’s Pretzel Tankard

By Amy Gillette, Research Associate

In the 1930s, Dr. Albert Barnes began collecting metalworks, furniture, and other everyday objects to galvanize the progressive educational mission of the Barnes Foundation, underscoring the connections between these objects and the “fine” arts of painting and sculpture.¹ One highlight of these utilitarian works stands on a small chest in Room 11: a sizable pewter drinking vessel called a tankard.

German. Tankard, 1766. 01.11.60. Public Domain.

Ensemble view (detail), Room 11, south wall, Philadelphia

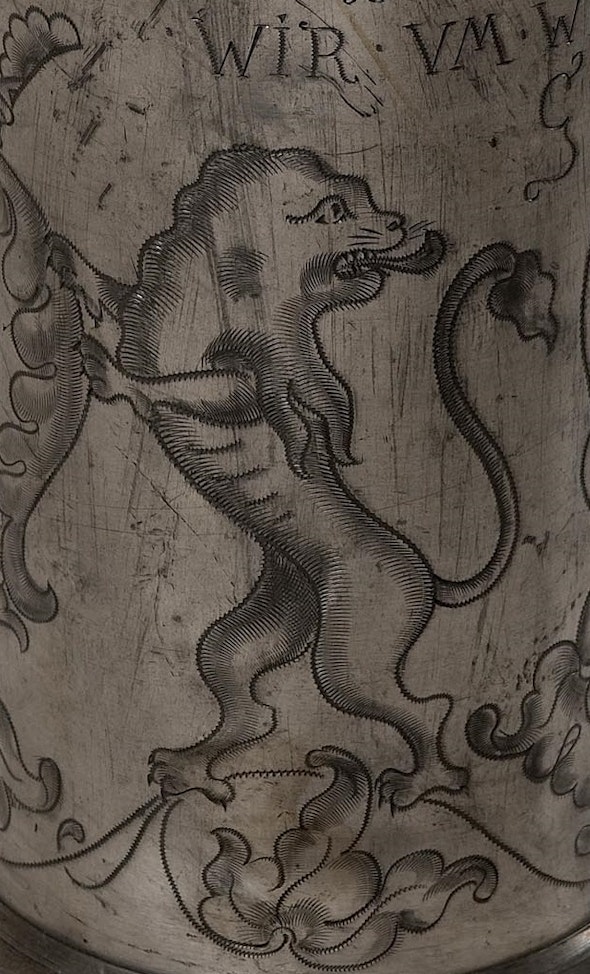

Probably used for beer or cider, the tankard rests on a molded foot and features an applied handle, a hinged lid, and a bulbous finial at the junction of the two. Its front is emblazoned with a pretzel bracketed by three loaves of bread and two lions rampant (standing in profile, with claws unsheathed) and topped with a jeweled crown. This design—the emblem of the bakers’ guild—is accompanied by two cheery inscriptions, in German, that announce the hopes of both patron and pewterer. The inscription surrounding the pretzel emblem reads: “May God in Heaven bless the field / Bake big bread so that we may make a little money.”² The one on the lid, encircled by a wreath of grain, declares: “Long live a well-crafted tankard, AD 1792.”³ Perhaps Dr. Barnes saw the tankard echoed in other works in the ensemble—its shape in the upright posture of Amedeo Modigliani’s Girl with a Polka-Dot Blouse (BF180) or the pretzel in the writhing trees of Chaim Soutine’s Group of Trees (BF331).

Chaim Soutine. Group of Trees, c. 1922. BF331. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Amedeo Modigliani. Girl with a Polka-Dot Blouse, 1919. BF180. Public Domain.

According to legend, the bakers’ emblem goes back to a Turkish siege of Vienna in 1683, when a group of bakers working overnight to prepare the morning’s bread discovered some Turks digging tunnels and planting mines.⁴ The bakers rushed to alert the city commandant, thereby thwarting the attack. The Austrian emperor gratefully awarded this crest to the bakers’ guild to honor the heroic bakers who saved Vienna from certain disaster. But this origin story is unlikely, as the crest’s key elements—crowned pretzels and loaves flanked by lions rampant—had been used on objects prior to 1683.⁵ Regardless, throughout the early modern period, bakers’ guilds persistently adorned their objects and buildings with the design on the Barnes tankard.⁶ The emblem has also been used on props for parades, shop signs, and even stained glass windows, and embraced by corporations as a symbol of piety and prosperity. The Snyder’s of Hanover pretzel company has perpetuated the motif into the present.

Surprisingly, the Barnes tankard seems to have received its engraving some 26 years after the vessel itself was made. Though the inscription reads 1792, its interior is stamped with the year 1766. Two figures adorn the interior, a man with a gun and an angel holding a scale and sword, both labeled E. M.—presumably the mark of the pewterer, who associated his initials and weaponry with the Archangel Michael (Erzengel Michael in German). Makers’ marks and further ornament were common inside German tankards.⁷

The Barnes tankard was probably made for private use, given its height (12.75 inches) relative to the monumental ones (usually 18–20 inches) designed for drinking rituals in guild ceremonies. These affairs were evidently quite convivial: when filled, the tankards were too heavy to be passed around and so were known as Schliefkannen (“vessels that have to be dragged”).⁸ One ornate Schliefkanne, c. 1560, belonging to a butchers’ guild in Zittau, Germany, stands over 20 inches tall and weighs nearly 30 pounds empty.⁹ Despite the size of the Barnes tankard, the Wir (“we”) in the 1792 inscription may suggest its use or reuse within a guild house.

Ceremonial tankards for bakers and butchers

German. Guild Tankard (Zunftkanne) or Schleifkanne, 1604. Robert Lehman Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Paulus Weise. Tankard of a Butchers' Guild, c. 1560. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Whichever festivities the tankard might have animated during its life as a drinking vessel, the oath—“Long live a well-crafted tankard”—on its lid warrants a consideration of the vessel’s making to better understand its historical meaning as well as its current place within a Barnes ensemble. The object is made of pewter, an alloy of metals consisting primarily of tin with small amounts of lead, copper, or antimony added for durability.¹⁰ The Worshipful Company of Pewterers in London, the official pewter guild, issued ordinances in 1348; they reveal that this metal was highly regulated and required professionals “expert and cunning in the craft.”¹¹

Pewterers would fashion their objects by casting the molten metal in a mold (a suitable method as pewter has a low melting point), by hammering the metal in plate form, or by turning it on a lathe (a common way to form tankards).¹² Ornament on pewter objects often included engraving (as the metal is relatively soft), wriggle work (the wavy outlines of flora and fauna of the tankard), repoussé in the forms of bosses or shields, and pointille, among other options.¹³

Detail of the etching techniques on the Barnes tankard.

In use since Egyptian and Roman antiquity, pewter objects were popular in sacred and secular settings up to the early 19th century.¹⁴ The earliest known reference to pewter for use in the Catholic liturgy was recorded at the Council of Reims in 803. By the late 12th century, pewter chalices and Communion plates were common.¹⁵ A few centuries later, the Parisian housewife’s guidebook Le Ménagier de Paris (1393) signaled that pewter cups and plates were popular among the middle and upper middle classes.¹⁶ At this same time, guilds began to assert their status and wealth by commissioning ceremonial pewter drinking vessels.¹⁷ Other pewter objects from the late Middle Ages were flagons, candlesticks, coffeepots, snuffboxes, processional staves, pilgrim badges, and a large range of tableware. Pewter remained common until glass and porcelain became more popular in the early 1800s—around the time that many guilds dissolved as well.¹⁸

Happily for the pretzel tankard, its material and ornament ultimately suited the identity of another institution: the Barnes Foundation. Dr. Barnes described his appreciation of “the so-called useful arts” and their connection to his educational mission in a 1948 letter:¹⁹

“We constantly maintain, in our books and in our teaching, that the great artists of all time have not been only the composers, painters and sculptors, but workers in the so-called useful arts like wrought iron, pewter, glass, pottery, etc. In fact, many years ago I threw a bombshell into the teaching of art by claiming that there was no essential difference between the fine and the household arts... I got the idea of proving my case by putting pieces of wrought iron immediately next to some of the best paintings covering the period from the 13th to the 20th centuries.”

Dr. Albert Barnes

Long live a well-made tankard!

Endnotes

¹See the introduction by Richard Wattenmaker in Strength and Splendor: Wrought Iron from the Musée le Secq des Tournelles, Rouen (Philadelphia: The Barnes Foundation, 2015) for the general history of the Barnes Foundation’s collection of metalworks.

²“SO GOTT IM HIMMEL / SEGNET DAS / FELDT” and “BACKEN GROSS BROT / WIR. UM.WENIG GELD”

³“VIVAT / EIN. EHRPAHR / HANTWERK. DER / BECKEN / 17 Ao Di92”

⁴Judith Dolkart, “Tankard,” in The Barnes Foundation: Masterworks (New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2012), 200. Also see Emil Braun, “Heroic Deeds of Bakers,” in The Baker’s Book, vol. 1 (New York: Van Nostrand, 1901), 25 (recounts the siege, but not the genesis of the crest).

⁵For example: Phyllis Emert, The Pretzel Book(New Hope, PA: Woodsong Graphics, 1984).

⁶E.g., a glass one of 1754 from Bischofsgrün on display at the PANEUM: Wunderkammer des Brotes. Outliers such as an undated tankard magnificently shaped as a pretzel witness scope for creative discretion. Cf. a shoe-shaped cup made for a shoemakers’ guild in Nuremberg, c. 1550. Anthony North, Pewter at the Victoria & Albert Museum (London: V&A Publications, 1999), 49, no. 12.

⁷H. J. L. J. Massé, Chats on Old Pewter (New York: Dover, 1971), 106.

⁸Pewter at the Victoria & Albert Museum 1999, 49.

⁹http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O76551/tankard-weise-paulus/

¹⁰“Pewter,” in The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts, ed. Gordon Campbell (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), noting: “The composition and standard of pewter was controlled by the guilds. The highest-quality pewter, used for flatware, contained 90–95% tin with small additions of lead and/or copper.” See Pewter at the Victoria & Albert Museum 1999, 8–9, for the history of materials used in the alloy.

¹¹Charles Welch, History of the Pewterers’ Company (London, 1902), vol. I, 3. Also Massé 1971, 77–82 and 133f.; Verster 1958, 39–48.

¹²Massé 1971, 56–59.

¹³Massé 1971, 123–125; Pewter at the Victoria & Albert Museum 1999, 13–23.

¹⁴Pewter at the Victoria & Albert Museum1999, 8–13, citing references to pewter by Pliny the Elder and Theophilus; also Massé 1971, 74–75.

¹⁵A. J. G. Verster, Old European Pewter (London: Thames & Hudson, 1958), 33–38; Pewter at the Victoria & Albert Museum 1999, 162–164, citing the Rationale divinorum officiorum (c. 1285) by Durandus as “perhaps the most archetypally medieval point of view: A golden Chalice signifies the treasures of wisdom that be hid in Christ. A silver Chalice denotes purity from sin. A Chalice of pewter denotes the similitude of sin and punishment. For pewter is as it were half way between silver and lead: and the Humanity of Christ, albeit it were not of lead, that is, sinful, yet it was like to sinful flesh. And therefore not silver: and although impassible for His own sin, passible He was for ours.”

¹⁶Massé 1971, 74–75; V&A 38–39.

¹⁷See “Shapes and Uses [of Pewter]” in The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts 2006; Massé 82–84.

¹⁸Massé 1971, 86–111.

¹⁹Albert C. Barnes to Charles Montgomery, letter, March 5, 1948, President’s Files, Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives; Montgomery was an antiques dealer and scholar specializing in pewter, who worked as director of the Winterthur Museum and as a curator and professor at Yale.