Veronese (Paolo Caliari). Baptism of Christ (detail), Mid-16th century. BF800. Public Domain.

Veronese’s ‘Baptism of Christ’

By Robin Craren, Curatorial Research Assistant, the Barnes Foundation

Have you ever wondered how Albert Barnes acquired his collection? Part of our research here aims to understand the full provenance, or ownership history, of each work of art. All museums do provenance research. This type of research—which often involves digging through documents like old letters, dealer files, and auction catalogues—can help confirm a painting’s attribution, if in question, or reveal trends in the artistic taste of collectors. In many cases, this research has even helped restore Nazi-era looted art to its rightful owner.¹ When thinking about Dr. Barnes’s collection, it is interesting to remember that many of the works had long, sometimes complicated, histories before they entered his collection and assumed their place in his ensembles. Here, we will focus on one such work—Paolo Veronese’s Baptism of Christ.

Veronese (Paolo Caliari). Baptism of Christ, Mid-16th century. BF800. Public Domain.

Our research into the Veronese began in 2017, when we received an inquiry from the Carnegie Museum of Art, in Pittsburgh. As part of its digital provenance project, Art Tracks, the museum was looking into the current whereabouts of the collection of the Earl of Northbrook, an important group of Italian, Dutch, Flemish, and French old master paintings. (Researchers sought to bring the collection together again—albeit digitally—to illustrate its dissemination throughout the world.) The Carnegie Museum has seven paintings formerly owned by Northbrook, and researchers had identified paintings from some 50 other museums and collections as originating from this collection; several, however, were still unaccounted for. They wondered whether a painting in our collection—Veronese’s Baptism of Christ—might have once belonged to Northbrook.

One of the main resources for the Carnegie researchers was an 1889 publication called A Descriptive Catalogue of the Collection of Pictures Belonging to the Earl of Northbrook. Though not fully illustrated, the catalogue provided provenance, exhibition history, and descriptions of the paintings in the collection, organized by schools (Italian, French, Dutch, and Flemish). In the catalogue, a painting by the artist Paolo Veronese was listed with the following description:

“In the foreground, to the left, is a river, with a grassy bank to the right. Christ stands in the water, with white and violet drapery round his hips. He bends forward, with his hands crossed on his breast, while St. John, kneeling on his left knee, pours water from a vase over his head. There are small nimbs [halos] round the heads of both figures. A white dove, surrounded by a bright light, hovers over the baptismal vase. Near by [sic], on the left, are the heads of two cherubim, and two angel boys above. The opposite bank of the river, with high trees, forms the background. Evening sky.”

A detail of the painting.

Veronese (Paolo Caliari). Baptism of Christ (detail), Mid-16th century. BF800. Public Domain.

This description matched our painting, as did the listed dimensions. Still, we couldn’t be sure it was ours, as there are several paintings by Veronese of this subject. The next step was research in the Barnes Foundation archives. Hunting through Dr. Barnes’s correspondence and records, we unearthed a certificate from the art historian August L. Mayer certifying that the painting was a genuine Veronese and that it had been in the collection of Sir Thomas Baring, a member of the Earl of Northbrook’s family. This confirmed that our painting was in fact the one mentioned in the 1889 catalogue.

Mayer’s letter mentioned something else interesting: the painting had also belonged to Sir Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds was an English painter known for his portraits of European aristocracy. From 1749 to 1752, Reynolds traveled the Continent studying art and painting portraits. During this time, he visited various cities throughout Italy, including Venice, where Veronese was active. Reynolds admired the works of the Venetian masters and left detailed observations and notes in his journals about their paintings, describing the methods and techniques he observed.² It is unknown where or from whom Reynolds purchased the painting, but it is clear the value that he placed on Venetian artists like Veronese. Reynolds’s collection was sold at a series of auctions in 1795, and our painting was purchased by someone named “Stainforth.” This may be Richard Stainforth, the son-in-law of Francis Baring.

The painting once belonged to Sir Joshua Reynolds, an English painter known for his portraits of European aristocracy.

Sir Joshua Reynolds. Self-Portrait, c. 1750. Oil on canvas. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund, B2002.11

Enter the Barings. The family’s English roots date from 1717, when John (Johann) Baring immigrated to Exeter from Bremen, Germany. By 1762, the second generation had taken over the family merchant business. His son Francis Baring (1740–1810) opened a branch in London, where he gained a reputation as a leading merchant banker. In 1803, his company, Barings Bank, would help finance the purchase of the Louisiana territory by the United States from France. In the 1790s, now a baronet, Sir Francis Baring started buying property in and around London and collecting paintings to fill the walls of his residences. Although he primarily collected Dutch and Flemish old masters, Baring acquired the Italian painting Baptism of Christ sometime after 1795. It is possible that the painting was a gift from his son-in-law, Richard Stainforth.

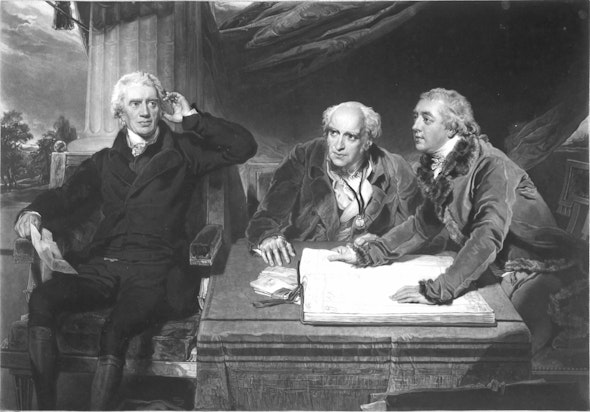

Famous banker Sir Francis Baring (left) acquired the painting sometime after 1795; it may have been a gift from his son-in-law.

James Ward, after Sir Thomas Lawrence. Sir Francis and Charles Baring, and Charles Wall, 1807-1811. Mezzotint, 1866. 1013.1962 © Trustees of the British Museum

Through inheritance and sales, the Veronese moved throughseveral generations of the Baring family. When Sir Francis Baring died in 1810,the collection was bequeathed to his son, Sir Thomas Baring (1772–1848). Afterselling 86 Dutch and Flemish old master paintings from his father’s collection toKing George IV, Sir Thomas Baring began to collect Italian and Spanish masters.His will stipulated that his collection be sold at public auction after hisdeath. When the time came, his son, Thomas Baring, MP (1799–1873), negotiatedthe purchase of many of the Italian, Spanish, and French paintings from theestate before the collection was sold. He also purchased a portion of hisfather’s collection of Dutch and French paintings at auction. As a second-bornson, Thomas Baring did not inherit his father’s title; he was a partner inBarings Bank, however, and therefore had the means to acquire a large portionof the collection.

After his death, in 1873, the artworks were inherited by hisnephew Thomas George Baring (1826–1904), the first Earl of Northbrook—and thepublisher of the catalogue in question. He was granted the title ViscountBaring and Earl of Northbrook in 1876 after serving as viceroy to India. TheEarl added to the collection as his uncle had, purchasing several importantportraits by the Flemish artist Anthony van Dyck. In 1904, at his death, thecollection again changed hands, going to his son, Francis Baring, 2nd Earl ofNorthbrook.

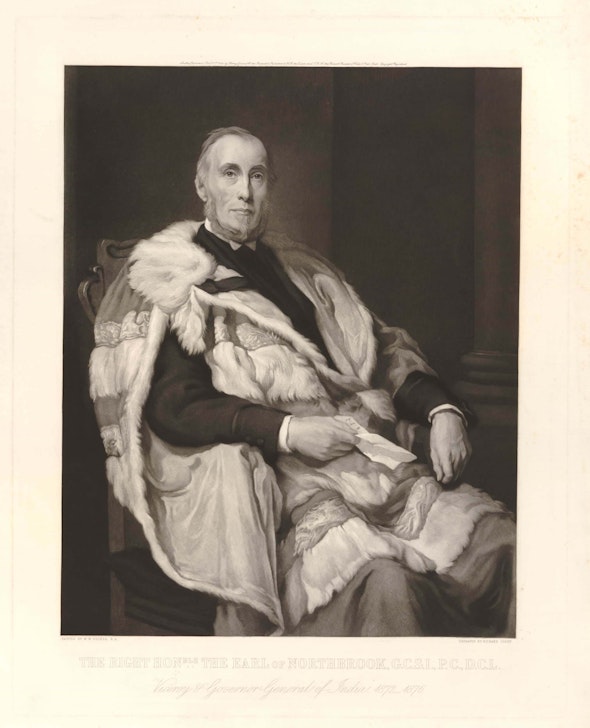

Thomas George Baring, the Earl of Northbook.

Richard Josey, after Walter William Ouless. The Right Honorable the Earl of Northbrook, GCSI, PC, DCL, 1884. Mixed method mezzotint. 2010. 7081.4444 © Trustees of the British Museum

A portion of the collection of the 2nd Earl of Northbrook wassold at auction in 1919. Our painting, Baptismof Christ, was purchased by a “Dowdeswell”—possibly Charles WalterDowdeswell, an art dealer who worked with his father, Charles William, atDowdeswell & Dowdeswells in London. Their partnership ended around 1912, atwhich point Charles Walter began working for London’s Duveen Brothers. He mostlikely purchased the painting for Duveen Brothers; the firm was a knownpurveyor of old master paintings and bought several important paintings fromthe 2nd Earl of Northbrook later in 1927.

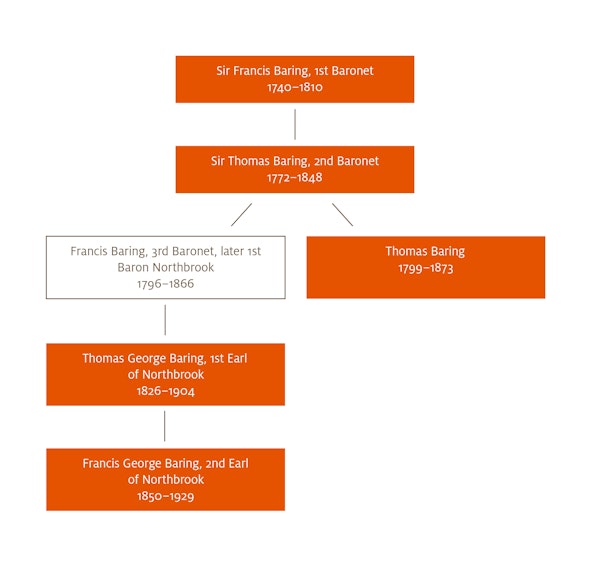

Through inheritance and sales, the Veronese moved through several generations of the Baring family, highlighted in orange.

There are sometimes gaps of knowledge in provenance research. Annotated sale catalogues help identify owners but, as shown here, rarely offer full names. Because of this, the painting’s ownership from 1919 until 1926, when Dr. Barnes acquired it, is unclear. Correspondence in the Barnes archives tells us that he purchased the painting from Count Alessandro Contini, who brought the painting to the Barnes Foundation for examination in December 1926. Through archival research, we were able to find a connection between Contini and Duveen Brothers that suggests that Contini obtained the painting from Duveen Brothers in 1925. In the dealer’s correspondence, an agent visited Contini to see his collection of old masters and Contini proposed that they should “do business” with one another.³ Unfortunately, we cannot confirm the sale without further information, which is often impossible to find.

Today, Veronese’s Baptism of Christ hangs alongside canvases by French modernist Odilon Redon and 17th-century Dutch artist Jan van Goyen on the north wall of Room 14. Before it found its final place in Dr. Barnes’s ensemble, the painting moved from Italy to England and then back again. It was displayed in an 18th-century mansion atop Richmond Hill in London, studied by a famous English painter who favored Venetian art. It hung in the Baring country estates of Stratton Park and Norman Court and various London homes, passing down through sale and inheritance through generations of one family as they rose to prominence. After finding its way back to Italy in the 1920s, the painting moved by ship across the Atlantic and by train to the newly established Barnes Foundation to be used as an educational tool by its founder.

The Veronese as it hangs today (second from left) on the North Wall of Room 14.

Ensemble view, Room 14, north wall, Philadelphia.

Endnotes

¹Although this research has always been performed by scholars, in recent decades, this work has been spearheaded by 1998’s Washington Conference on Holocaust Era Assets and the desire to identify unrestituted artworks. The issue of unrestituted art of the Nazi era emerged in the 1990s as the Cold War ended and war records began to be declassified, allowing access to previously inaccessible or hidden documents to shed further light on the provenance of objects confiscated, sold, or looted prior to and during the war. As part of this movement, museums and institutions have sought to fill in the gaps in provenance in their collections, particularly in the years 1933–1945. This has led to a stronger desire of art collectors and institutions to determine the provenance of works in their collection, regardless of their possible relation to the looting of the Nazi era

²Biographer Robert Charles Leslie notes that Reynolds did not leave these detailed notes for works in Rome and Florence implying a preference of the artist to the artists of the Venetian Renaissance, Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese

³Files regarding works of art: Contini Collection, Rome, ca. 1925–1926, Duveen Brothers records, 1876–1981 (bulk 1909–1964). Series II. Correspondence and papers. Series II.A. Files regarding works of art, GRI Digital Collections